Alfalfa has long held a tenuous position in the grazing world. Many pasture enthusiasts want nothing to do with it. Others may include it in paddocks at a low density. Finally, there is a miniscule group of brave souls who utilize alfalfa as a major component of their grazing systems — and their cattle thrive on it.

Beef and forage researchers at Iowa State University (ISU) have initiated a study to evaluate three so-called grazing-tolerant alfalfa types. Erika Lundy-Woolfolk, Beth Reynolds, and Shelby Gruss offered first-year results from their alfalfa trial in a recent Growing Beef newsletter.

“Traditionally harvested as hay, alfalfa has been less favored for grazing because of bloat concerns and its limited persistence in pastures where hoof traffic can damage the plant’s crown,” the researchers contend. “However, with current economic pressures prompting cow-calf producers to extend the grazing season and reduce reliance on stored feeds, newer ‘grazing-friendly’ alfalfa varieties have been developed. These varieties not only lower the risk of bloat but also feature improved root structures, such as creeping roots or sunken crowns, to better withstand hoof traffic.”

The ISU study is assessing alfalfa forage yield, quality, and stand persistence of grazing-tolerant varieties. Some of these varieties offer reduced bloat risk and root structures that are less prone to hoof damage. Three distinct types of alfalfa are being evaluated:

Creeping-root alfalfa – Known for a creeping root or rhizomes. This type is known for spreading across pastures to improve growth and persistence.

Sunken crown alfalfa – Compared to the traditional varieties, the plant’s crown grows below ground, offering improved tolerance to hoof traffic and better protection from winter damage.

Falcata alfalfa – With a unique yellow bloom, this type has a fibrous root structure, continues to grow after flowering, and is a winterhardy, more drought-tolerant alfalfa option.

Methodology and results

The study was established by seeding alfalfa at a rate of 7 pounds per acre and grass at 10 pounds per acre to achieve a target stand composition of 40% alfalfa and 60% grass. One year after planting, the plots were rotationally grazed throughout the summer of 2025.

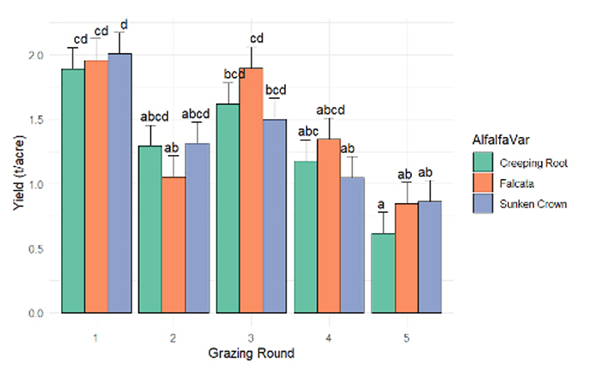

Five locations within each plot were selected for persistence tracking, and a regression model was developed to evaluate the alfalfa varieties at each grazing event. The analysis revealed significant effects from grazing events or rounds. Round 1 (late May) had the highest yield at 2.05 tons per acre, while the subsequent three rounds averaged between 1.2 and 1.6 tons per acre (see Figure 1). There was no statistical yield difference associated with variety.

Figure 1. Alfalfa yield by grazing round for three alfalfa variety types. Letters indicate significant differences.

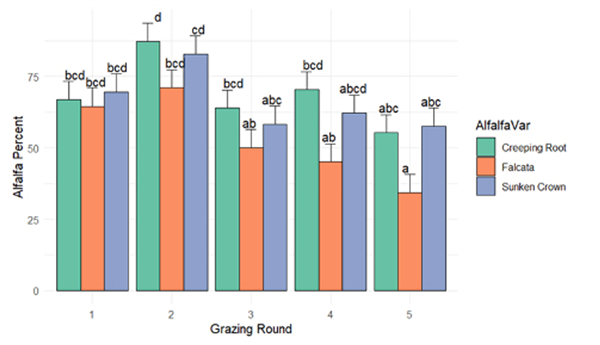

A mixed-effects model was used to evaluate how alfalfa variety and grazing round influenced the percentage of alfalfa contributing to total yield. There was a significant effect for both grazing round and alfalfa variety, although their interaction was not significant (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Percentage of alfalfa by grazing round for three alfalfa variety types. Letters indicate significant differences.

As described by the trio of researchers, grazing round influenced alfalfa percentage, with Round 2 (early July) showing a significantly higher proportion of alfalfa in the stand. The falcata variety contributed 53% of the total yield, which was notably lower than creeping root (68%) and sunken crown (63%).

From the first grazing round to the last, falcata was the only variety with a significantly lower percentage, but this may be more due to its fall dormancy rating of 2 than because of grazing pressure. To fully understand the effect of grazing on the alfalfa varieties, the researchers plan to make stand assessments during the spring. This will offer a greater understanding of the alfalfa persistence within the stand.

The researchers note that the alfalfa persisted well throughout the first grazing season even though establishment was a problem in some areas. Where good germination and establishment was achieved, stands exceeded the 40% alfalfa density target.