As regulations for food animal production change, interest in growth promoters for cattle is growing. In past decades, the growth promoters were antibiotic or synthetic chemicals; however, we are now finding that natural plant compounds can be used to enhance gain-to-feed ratios in ruminants. Better yet, the compounds can come from forage plants.

Our group, the USDA-Agricultural Research Service Forage-Animal Production Research Unit, has discovered an antimicrobial growth promoter in red clover. The compound, called biochanin A, belongs to a family of chemicals called isoflavones that are found in many legumes. To fully appreciate how biochanin A works, we have to understand how antimicrobial growth promoters work in general.

HAB control

The feature that makes ruminants special is the rumen, the fermentation vat of the stomach that is home to some of the most amazing microorganisms in the world. These microorganisms break down fiber, which gives ruminants access to energy that nonruminants simply cannot use. Without the rumen microorganisms, ruminants could not get enough energy from fiber, and their diets would be more like diets for swine or other nonruminant species.

However, the fiber-digesting bacteria are not the only microorganisms in the rumen. Others attack and digest almost every component of the feed. Most of them are helpful or at least harmless, but the bacteria that digest protein take more than their share. These bacteria convert the amino acids that make up protein to ammonia, which is where they get the name, hyper ammonia-producing bacteria (HAB). When the protein is converted to ammonia, much of it is absorbed into the blood and converted to urea. When you apply nitrogen fertilizer to boost the protein in your grass, as much as half of it can be urinated back onto the ground. You have the HAB to thank for that.

This is where antimicrobial growth promoters come in. A selective antimicrobial can kill the HAB without harming fiber-digesting bacteria and other beneficial microorganisms. When HAB are inhibited, more protein is available to the animal, and gain-to-feed improves. You can think of this in the same way that you think of an herbicide. An herbicide is sprayed to selectively eliminate weeds and leave the plant species we want.

Likewise, an antimicrobial growth promoter is fed to selectively inhibit wasteful rumen microorganisms and direct nutritional resources where we want them to go. Some feed additives that we think of as antibiotics and coccidostats are also antimicrobial growth promoters, which is why we see growth rate or feed-efficiency improvements in healthy calves that don’t have infections or coccidiosis.

Red clover shines

Biochanin A, the isoflavone from red clover, passed all of our laboratory tests. It reduced ammonia production from valuable amino acids and protein.

We are also currently exploring the effect of biochanin A on other beneficial groups of microorganisms in the rumen. We knew that biochanin A would be safe for cattle because the beneficial dose was within the range that we see naturally in Kenland and other red clover cultivars. The initial grazing trials were conducted with steers grazing a mixture of orchardgrass, Kentucky bluegrass, and endophyte-free tall fescue. Each steer also received daily 3 pounds of dried distillers grains (DDG) either with or without purified biochanin A mixed in.

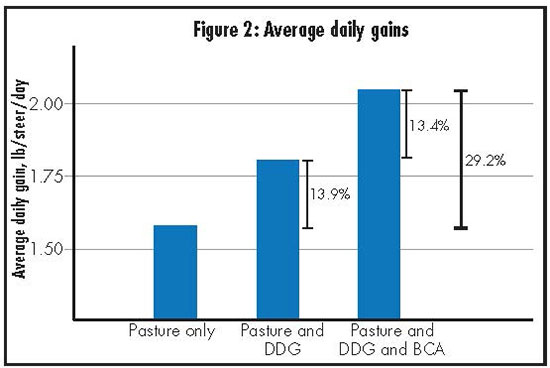

The study was conducted in the spring and fall of 2015 with two different sets of steers. Each 2.5-acre pasture was grazed with four steers, and each treatment was replicated three times. Figure 2 shows that DDG without biochanin A improved average daily gain 13 percent relative to the pasture-only treatment, but adding biochanin A to the DDG boosted average daily gain 29 percent compared to the control. This suggested that adding biochanin A to the protein supplement improved the quality of protein available to the steers.

Questions remain

Red clover has long been an important pasture legume and high-protein diet component, and the effects of biochanin A might explain the production benefits that go beyond protein content. However, there are new considerations if red clover or other legumes are to be used as a source of antimicrobial growth promoters. First, it is important to know that biochanin A and other isoflavones are phytoestrogens. In high doses, they can mimic the positive and negative effects of estrogens. Grazing red clover can lower the fertility of cows and sheep. Another consideration is how to best deliver the biochanin A to growing steers. Grazing is the obvious choice for many, but a 20 to 40 percent clover stand will likely be necessary to obtain the benefits of clovers on calf performance.

We are presently conducting a grazing trial that delivers low and high doses of the isoflavone through consumption of the clover. Our future research will evaluate the optimum dose of biochanin A to achieve the maximum response by the animal. This research will give us a better idea of the range of clover percentages in mixtures with grasses needed to accomplish improved performance. Our current work indicates that biochanin A is stable in red clover hay, but we do not know how forage quality, harvesting, and environmental factors impact stability.

This article appeared in the February 2017 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 30 and 31.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.