Grass-fed beef is a growing niche market that provides opportunity for marketing cattle with enhanced value. In the Upper Midwest, selling grass-finished beef in local markets can also take advantage of the growing popularity of local foods. However, there is more to producing high-quality grass-fed beef than simply keeping cattle on pasture without grain. Successfully finishing beef on forage requires a radical shift to the way many beef producers think about forage quality. Say goodbye to the idea of “beef-cow quality” forages and hello to “dairy quality.”

Finish them fast

Grass-fed systems require premium quality forages that push animal performance to a high level at every step. Because a winter “white season” with dormancy of forage growth is unavoidable in the Upper Midwest and stored forage is almost always more expensive to feed than pasture, profitability demands that grass-finished cattle in this region are marketed before their second winter.

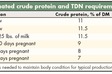

In order to finish a steer to acceptable carcass size and quality in two growing seasons on grass, there is no time to waste on periods of backgrounding or poor gain. Cows should produce enough milk to wean a calf weighing about 600 pounds at 205 days. In order to reach finishing weight of 1,200 pounds by 19 months of age, this calf must then gain at least 1.25 pounds per day. Research shows that if gain drops below that level, it takes too long to gear back up when optimal nutrition is restored. An inconsistent rate of gain over the lifetime of the steer also reduces meat quality.

In grass-finished systems, it may be easier to successfully finish smaller framed cattle than the feedlot industry norm; they can reach an acceptable level of finish and marbling at a younger age. It is also helpful if the cattle genetics have been specifically selected for good performance on

forage-only diets.

In Michigan State University research from northern Michigan, Red Angus-influenced cattle bred for grass-finishing systems routinely finish to a high Select grade in 19 months with a final body weight of 1,200 pounds. These cattle typically have frame scores from 3 to 4. However, cattle of differing genetics have also been successfully finished with this system in northern Michigan, suggesting that forage management is more important than cattle genetics.

Keep hay quality high

Any hay or baleage offered to finishing cattle in the winter or as a pasture supplement needs to be premium quality. Making high-quality hay is never a guarantee because sometimes Mother Nature doesn’t cooperate. It always requires a sizable time commitment. Producers with full-time, off-farm jobs or limited time and funds to put into haymaking enterprises may be further ahead if they purchase high-quality hay from someone else rather than to try to make do with their own hay crop of average quality.

High-energy pastures

Grass-fed cattle are going to spend most of their time on pastures. In general, cattle that eat more energy gain faster. Premium quality forage is high in energy. Nevertheless, when forage quality on pasture is mentioned, the first thing that usually comes to a grazier’s mind is protein. Sometimes, low-quality warm-season grasses or overmature forages are indeed low in protein. However, in the Upper Midwest, cool-season grasses and legumes dominate pastures, and these forages almost always contain more than enough protein to meet the needs of growing cattle.

The most limiting nutrient on these pastures is usually energy. Forages that are high in energy generally contain less cell wall, or neutral detergent fiber (NDF), and more sugars and other highly digestible components (NFC, or nonfiber carbohydrates). It’s easy to do this when grain is included in rations, but of course that’s not an option for grass-fed cattle.

So, how do we maintain high-energy intakes on forage alone?

One approach is to manage pastures for less NDF. The percentage of NDF in forages escalates with plant maturity and that NDF gets less digestible. Both of these changes reduce the TDN (total digestible nutrients) available in the forage and lowers dry matter intake. Therefore, grazing forages while in the vegetative stage (before flowering) provides more energy.

Another approach is to include legumes in the pasture mixture because digestibility of legumes is usually greater than grasses. In the Michigan State University grass-finishing system, acceptable grass-fed gains require NDF values to be less than 45 percent. This type of forage typically has an RFV (relative feed value) of 150 or more and can support 2 pounds per day of average daily gain. Low fiber and high RFV is maintained by using a rotational stocking system with a stocking rate of one steer per acre.

Need to finish strong

The last six to eight weeks of finishing presents the greatest challenge to profitability in a grass-finished system. Growth rate of the cattle naturally slows as they near adult size, and energy intake is applied to marbling and fat instead of muscle and bone. With spring calving systems, the final phase of pasture finishing is right at the time of year when perennial pasture growth is slowing down in preparation for winter. While forage quality in fall may be exceptionally high due to cool weather that elevates sugar content, the quantity of forage available is often limiting.

Therefore, a second approach to boosting energy intake in pastured cattle is to grow annual forage species that tolerate cool weather and can provide the energy needed for final finishing. Brassicas are often used for extending the end of the grazing season because of their excellent cold tolerance. They also have excellent feed quality, being highly digestible, very low in NDF and high in NFC. Brassica pastures can easily have NFC concentrations comparable to corn silage.

Brassicas are essentially high-moisture concentrate feeds, but they are a concentrate that is totally acceptable for grass finishing. However, the high- moisture content may be a drawback that potentially limits forage dry matter intake simply because the gut is full of water. Pure brassicas also may contain inadequate ruminally effective fiber to support rumination and prevent ruminal acidosis. Therefore, dry hay or access to perennial pasture should be provided to cattle on brassica pastures.

An easy solution is to grow brassica mixtures with a grass like oats or other species designed to provide effective fiber. The transition period is an important consideration when moving cattle to brassica-based pastures. No producer would abruptly switch cattle from a grass pasture to a feedlot diet, yet this is essentially what happens when cattle walk through the gate from the perennial pasture to the brassicas. Transition cattle gradually to such a drastic diet change by slowly offering brassicas for longer increments of time each day and providing a premium quality hay supplement.

Attention to forage quality will pay off in a grass-finishing system.

This article appeared in the April/May 2017 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 8 and 9.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.