The author is assistant professor, department of dairy science, Virginia Tech.

We had concerns

In addition, as financial budgets may be tight to purchase high-quality alfalfa hay, we included poor-quality mixed-grass hay (10.1 percent crude protein, 70.6 percent neutral detergent fiber, and 4.7 percent lignin) typical of our Southern region. Finally, the experimental diets included either brown midrib (BMR) forage sorghum silage or conventional (non-BMR) corn silage.

Prior to running the experiment, we had a few concerns about these atypical diets. For example, feeding poor-quality hay might reduce voluntary feed intake, resulting in a corresponding lack of production performance. Also, combining a low-forage diet with a grain source of rapidly fermentable starch might result in subclinical ruminal acidosis with a consequent milk fat depression. Finally, from our experience in the field, we were concerned that cows consuming sorghum-based diets would eat less feed than cows consuming corn-based diets. Theoretically, this expected difference in feed intake would have translated into differences in milk yields.

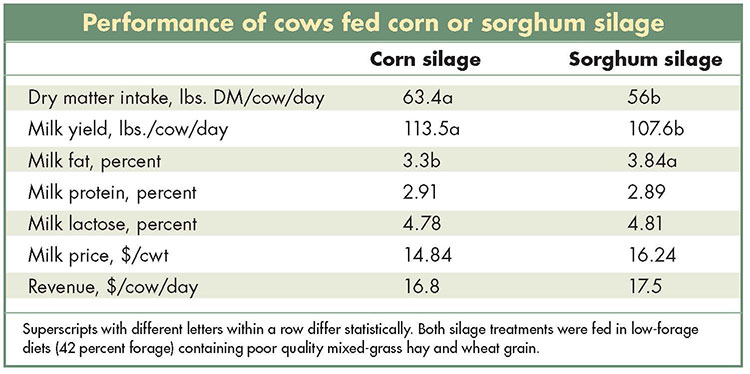

The first interesting observation of this study is that milk yield was more than acceptable (see table) regardless the type of silage fed. Obviously, the high milk production can be related to the physiological stage of these cows that were at 50 days in milk at the beginning of the experiment. However, it is still quite promising to know that high milk production can be sustained without dependence on alfalfa hay and corn grain. Cows consuming the corn silage-based diet produced about 6 more pounds of milk than cows consuming sorghum-based diets.

This difference in production was likely related to the greater dry matter intake for corn silage. So far, the differences in dry matter intake and milk production highlight the use of corn silage. However, cows consuming the sorghum silage-based diet had a higher concentration of fat in milk than cows fed the corn silage-based diet.

Economics favored sorghum

The difference in milk fat test is not a trivial observation since maximizing milk fat concentration is critical to a higher milk price. Considering a milk fat price of $2.6635 per pound and a Class III skim milk pricing factor of $6.25 per hundredweight (cwt.), the resulting milk price would be about $1.40 per cwt. greater for cows consuming sorghum silage-based diets than for cows consuming corn-based diets.

As pricing silages can be tricky and subjective, I decided to stop the analysis here. However, it’s logical to claim that sorghum silage is cheaper, or of similar value, than corn silage. Under this scenario, feeding sorghum silage-based diets can be a useful and favorable economic strategy.

In summary, independent of the type of silage utilized, feeding low-forage diets with poor-quality hay and wheat as the grain source proved to be a successful strategy for sustaining milk production and potential revenues. These strategies, as well as many other ones, could help to attenuate the adverse effects of drought.

Many people, including farmers,

consultants, or extension educators, might have forgotten about past drought events. My colleague from University of Kentucky, Chris Teutsch, once said, “Every drought seems to be a surprise.” Our purpose for this study was to identify feeding options in response to the next severe drought. Even though we cannot know when, we can be sure droughts will happen again.

This article appeared in the August/September 2018 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on page 23.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine