If you ask Eric Bailey what the most important factor is for combatting the rise in beef cow costs, his answer will be to control supplementation.

To make that happen, the University of Missouri extension beef nutrition specialist emphasizes the importance of syncing up your pasture and forage resources to the cows. “We need to make sure that the pasture provides as much of the cows’ nutritional needs as it possibly can,” he said at the Cattlemen’s College, which was held in conjunction with the Cattle Industry Convention and National Cattleman’s Beef Association (NCBA) Trade Show.

Bailey pointed out that spring calving has somehow evolved to dropping calves in January or February in many areas. “There are reasons why we might want to calve in the winter, but in most forage systems, we’re going to have the cow’s nutritional requirements peak before the grass quality and quantity reach the point where it’s going to help.”

Of course, matching forage with nutritional needs is specific to where you hang your hat.

Bailey noted that in a rangeland, warm-season grass dominated the environment where cows calve in February, there’s a large amount of time that passes before the grass reaches its energy-providing peak in early May.

“If we shift the calving season 60 days later in April, our supplement needs during winter decline dramatically and the cow’s peak nutrient requirements match the grass’ peak forage quality,” Bailey said. “In fact, the cows might be in a nutrient surplus going into the breeding season,” he added.

Bailey pointed out that this strategy may not be as advisable in the southeast U.S. where breeding in the summer could be hindered by heat and humidity.

The Fescue Belt provides a scenario where fall calving may be more beneficial. “Where we’re dealing with toxic tall fescue, a spring-calving herd’s peak nutritional needs sync up to when the ergot alkaloids are highly concentrated in the fescue seedhead,” Bailey noted. “This can depress gain and reproductive performance. Fortunately, cool-season grasses have two forage quality peaks, and one of them is in the fall.”

In showing some data from the University of Arkansas, Bailey pointed out that the total digestible nutrients (TDN) of stockpiled tall fescue exceeds a lactating cow’s energy requirement from October through February. The protein provided by the stockpiled fescue is always above the cow’s requirement throughout winter.

Bailey noted that the biggest challenge with stockpiled tall fescue is quantity and making the resource last through the winter.

Although each operation’s situation and forage base are unique, Bailey asserted that the savviest cattle managers he knows have figured out how to match the cow nutrient requirement with their feed resources to help minimize supplementation costs.

Know your limiting nutrient

“Eight out of 10 calls I get from producers come with a question about vitamins, minerals, and additives,” Bailey related. “In many of those cases, the conversation really needs to be about feed intake because their hay quality is poor, or their pastures are short, and energy or protein intake is limiting.”

The beef specialist noted that one of the foundational mistakes that many producers now make is not adjusting historical stocking rates for today’s larger animal. As a result, they come up short on feed.

“Protein is often the first limiting nutrient in warm-season rangelands,” Bailey said. “Protein is not the most limiting nutrient in many other parts of the country. In Missouri, for example, even poor-quality tall fescue often has adequate protein to meet mature cow requirements. Protein does not cure poor hay, which is routinely fed all across the South; energy is the limiting nutrient in many instances,” he asserted.

In Missouri and many other states, making and feeding hay is a normal practice. “Our problem is that in many cases the hay we try to make in May doesn’t actually get harvested until June because of weather problems or prioritizing other jobs before haymaking,” Bailey said. “The result is that often we find ourselves with a large stockpile of poor-quality hay.”

Supplement appropriately

“Once protein percentage gets below 7%, feed intake drops off dramatically,” Bailey related. “Protein is needed by the bacteria in the rumen. If their protein requirement is not met, this impacts fiber digestion, slowing down passage through the rumen and reducing feed intake.”

Bailey recommended pricing protein supplements on a cost per pound of crude protein basis. “This gives us an apples-to-apples comparison across various supplements,” he said.

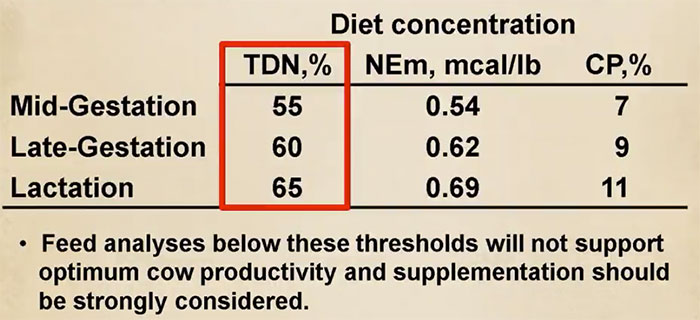

Meeting the cow’s energy needs can be a little more complicated than protein, but it’s often the limiting nutrient when poor-quality forage is fed. Bailey likes to follow these simple rules of thumb developed by the Noble Research Institute:

Unlike protein, Bailey reminded the audience that energy supplementation needs to be done on a daily basis for it to be most effective.

“A cow will eat 2.5% of her body weight per day,” Bailey said. “When you’re providing extra energy, I try to get producers to supplement about 0.5% of body weight per day as a starting point. But this can vary based on forage quality, nutrient requirements, and the supplement used. It’s best to work with a nutritionist to fine-tune your energy supplementation program,” he added.

To conclude, Bailey again encouraged producers to match animal nutrient needs to pasture growth and quality. By doing so, supplementation needs can be minimized. In many cases, making better quality hay can also do the same.