It is no secret that improving forage quality will improve animal performance and probably lower costs due to less need for supplemental feed. There are many components of forage quality, but the two this article will focus on are crude protein and energy, or total digestible nutrients.

When many ranchers discuss improving crude protein in introduced forages, they often talk about using fertilizer, particularly nitrogen. This seems logical since crude protein is directly proportional to the percentage of nitrogen in the plant. However, like many other things that seem logical but are not, this is not the case. Proper fertilization of introduced forages results in more forage but not necessarily better forage.

I conducted an experiment from 2008 to 2010 to look at how fertilization affected yield and quality of bermudagrass. The test consisted of nine varieties of bermudagrass fertilized with five rates of nitrogen. Plots were harvested every 30 days.

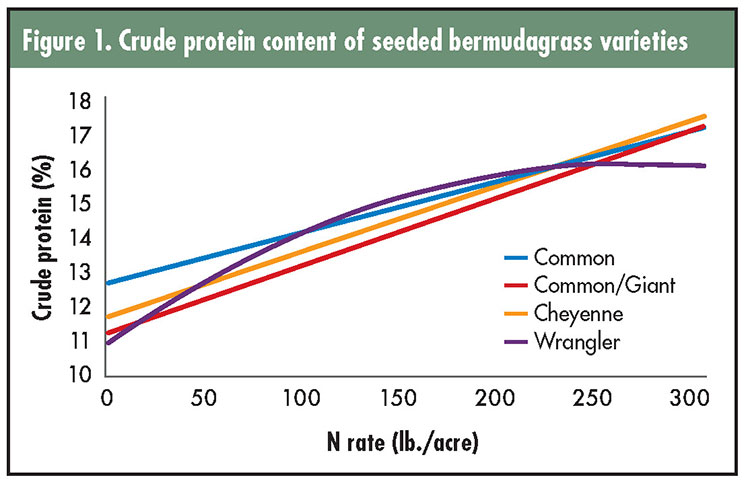

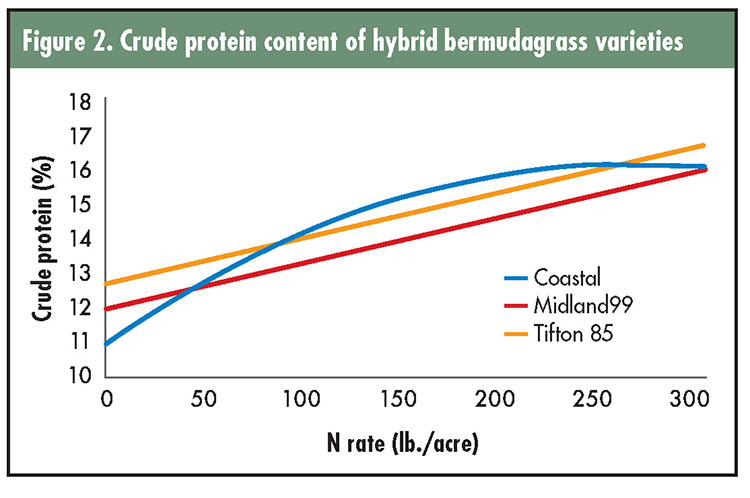

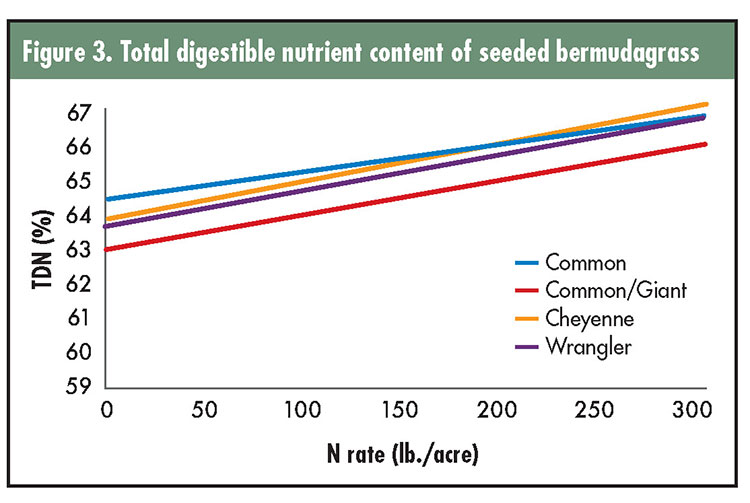

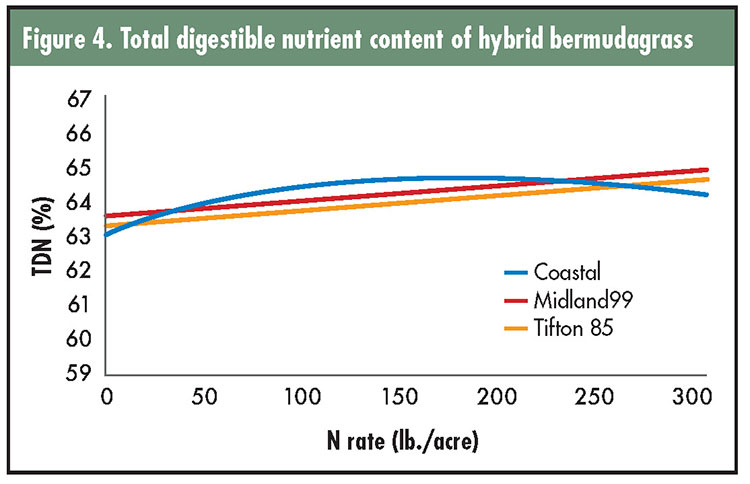

As expected, yields increased with fertilizer. Crude protein also improved with the addition of nitrogen fertilizer but not as much as many people might think. In this test, applying 100 pounds actual nitrogen per acre boosted crude protein by 1% to 2%, shown in Figures 1 and 2. Figures 3 and 4 show that total digestible nutrients increased even less than crude protein when fertilized with nitrogen (0.5% to 0.8%). It appears that fertilizing is an expensive way to boost forage quality.

We had excellent forage quality in our test. During the three-year period, we did not experience crude protein levels less than 11% or total digestible nutrients less than 62.8%, even in the unfertilized check plots. This shows that something besides fertilizer is responsible for forage quality.

Plant maturity rules

The most important factor in forage quality is the maturity of the plant when it is harvested. The younger the plant, the higher the quality for both crude protein and total digestible nutrients. As plants mature, lignin, which is mostly indigestible, is deposited into the cell walls. The higher the lignin content, the lower the digestibility of the plant.

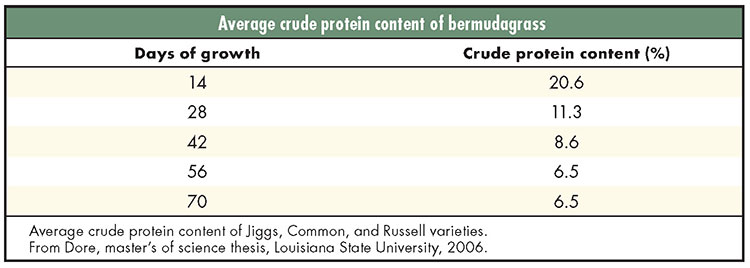

The decline in digestible nutrients is most pronounced in tissue of warm-season perennials, such as bermudagrass, that is older than 35 to 40 days. Research at Louisiana State University showed the decline in crude protein as bermudagrass plants matured (see table below). Crude protein content declined rapidly until growth reached 56 days but stabilized after that point.

How can ranchers use this information to improve the nutrition of their herds?

Grazing management and hay harvest timing can make huge differences. Graze forages when plants are in a growth stage that is high quality. This is most easily done by implementing rotational grazing to ensure that cattle are eating forage that is less than 30 days old at all times during the growing season. In bermudagrass hay production, harvest every 25 to 30 days to achieve the best compromise of forage quantity and quality.

There is often a forage quality slump in introduced warm-season perennial forages in late fall and early winter. One way to avoid this is to stockpile standing hay. In this system, graze or mow a field short in August, then defer grazing until the plants go dormant after a freeze. The forage that grew during the fall will be high quality since it is all new growth and can be grazed after dormancy, possibly reducing hay feeding by one to two months.

Attaining higher forage quality can improve animal performance and reduce supplemental feeding. The best thing — it is simple and relatively inexpensive to achieve.

This article appeared in the August/September 2020 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 28 and 29.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine