Every good baseball or football fan knows that the offseason is when decisions are made that often dictate future success or failure. It’s a time of reckoning and planning. The offseason is also a time when the tough questions need to be asked.

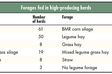

Did we put up enough high-quality forage? What do we need to do differently next year? Is our ace pitcher washed up, and is it time to trade for a new chopper? Do we have a kicker missing the easy field goals, and are we not getting the feed piles covered on time?

Assemble the team

At the end of the year, the owner and key managers need to bring their forage team together. Internally, the crop and operation managers are the starting core. But think further than just the planting and harvesting.

Invite your internal numbers guru, who can address finances, including the variable costs of raising forages and capital expenditure analytics. Invite the herd manager, who can address the importance of “clean” feed on herd performance. From the outside, bring in your agronomist and dairy nutritionist. Historically, agronomists and nutritionists have only waved at each other from across the feedbunk but need to walk hand-in-hand from the field into the freestall barn. Include in your meeting a trusted supplier representative, and finally, don’t forget your banker, who brings insights from other farms.

The forage closeout

A closeout in a livestock feedlot is a final reckoning of performance and profitability of a group of cattle; it’s as common as a politician in Iowa during the political primary season. But how do we measure success and profitability in our forage program?

I often ask when putting a ration together, “What number should I use for your cost of corn silage in the ration?” The sound of crickets are sometimes followed by, “What do you use on other farms?” Sometimes I will get the standard answer of 10 times the price of corn. To push this issue harder, I usually ask, “Is that dollars per ton of dry matter or as fed? Is that before or after fermentation shrink? Does that include depreciation on storage facilities?”

A forage closeout needs to begin with trusted data and common terms. Begin by always talking from the standpoint of dry matter tons. For example, convert yield from 20 tons per acre of corn silage to 7.3 tons of dry matter.

Agronomists and nutritionists need to agree on forage quality measurements. I don’t know of any dairy nutritionist who has ever used relative forage quality (RFQ) to balance a dairy ration. More useful terms like 7-hour starch Kd, 30-hour neutral detergent fiber digestibility (NDFD), and ash content are linked more directly to cow performance. It’s like baseball junkies moving from runs batted in (RBI) to on-base plus slugging percentage (OPS) and wins above replacement value (WAR). For the record, I’m still stuck on RBI, too, but my point is that common terms are needed to reach common goals.

Closeouts need accurate, trusted forage production data. Unlike beef closeouts, we can’t just take an inventory at the end of the year because forage is constantly being used. For long-term success, large dairies will need to have on-farm scales to measure feed as it arrives on the farm and a sampling protocol. Without a scale, inventories can be estimated from bunkers and piles, but errors of 10% to 30% are common due to variation in packing density. If there is an accurate beginning inventory, feed software can bridge the gap to shrink and usage rates.

Decision making

This is where the entire team becomes important. Herd managers and nutritionists will often want to maximize milk production with high-quality forages. Crop managers must weigh greater capital and variable costs to produce this feed. For example, if a dairy buys their own chopper and reduces their time of chopping corn silage from 17 to seven days, will the consistency and quality improvement cover the additional cost for the harvester?

By having the team together, a good discussion can be had about paybacks on agronomy decisions. If spraying a fungicide helps in two out of five years to reduce mycotoxin loads, does it really make sense? Everyone has to be kept accountable. Put everything in dollars per year, which will assist in moving the discussion to an agreement.

Risk assessment

There are some dairies that always seem to harvest high-quality forage and avoid the pitfalls of machinery breakdowns, rain, and delayed custom haulers. They appear to be one step ahead. As forage teams become more advanced, a helpful exercise can be a risk analysis.

List all of the things that could go wrong in your forage program. Then weigh those problems by their likelihood and financial impact. If you are constantly having forage not packed correctly, that can have huge financial repercussions, so putting on another pack tractor would make good financial sense. If you had problems harvesting corn silage one time in 30 years because of rain, can you really justify the purchase of dump wagons?

Expenditures

Input purchases is a topic that has been intentionally left for the end. There is a remarkable disconnect in seed sales and field cropping decisions. It reminds me of the Kohl’s store sales my wife tells me about — “It’s on sale now for 30% off but only until Friday,” she relates. This is a well-defined, high-pressure sales tactic. Complete a forage closeout, plan, and then purchase. Decisions such as brown midrib (BMR) corn versus non-BMR need to take place before the purchases begin.

The offseason is here; get your team ready to forage.

This article appeared in the November 2020 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on page 7.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.