The U.S. haymow is about 12% emptier today than it was one year ago.

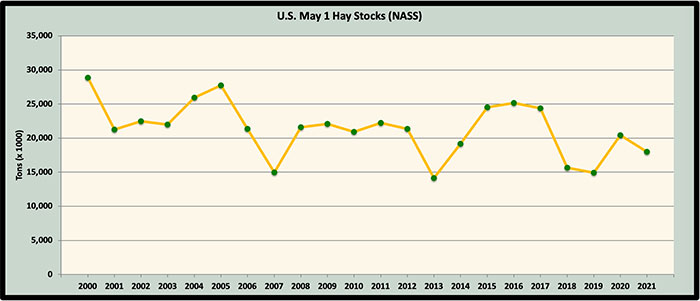

Based on USDA’s Crop Production report released last week, May 1 hay stocks dropped by almost 2.5 million tons. This follows a 37% boost in May stocks from 2019 to 2020 after nearly hitting an all-time low in 2019.

Hay stocks currently stand at just over 18 million tons. This past December, year-over-year hay stocks declined only slightly from 2019.

At 18 million tons, May 1 hay stocks are still above 2018 and 2019 stocks but are far below the hay inventories of 2015 to 2017.

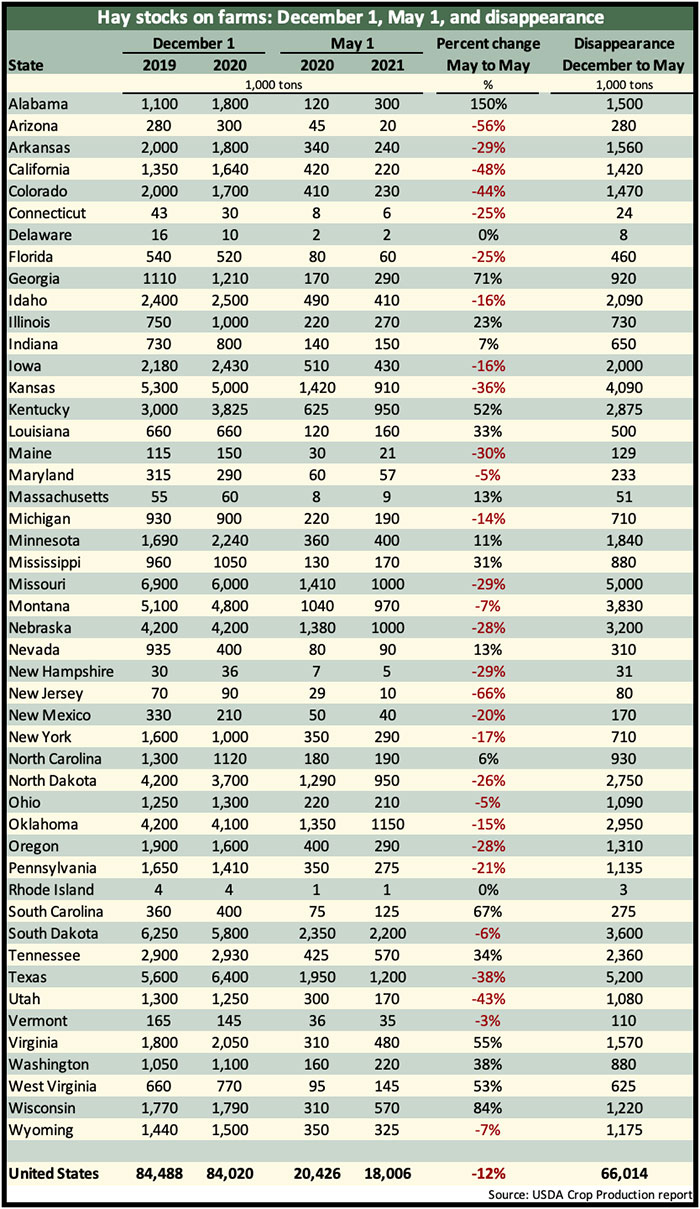

Many of our largest hay-producing states, especially in the West, had significant year-over-year May 1 stock declines (see table below). According to The Hoyt Report, Western states had their lowest May 1 stocks since 2014. States with some of the largest declines include:

Arizona: down 56%

California: down 48%

Colorado: down 44%

Utah: down 43%

Texas: down 38%

Kansas: down 36%

On the flip side, there were also some major hay-producing states with significant inventory gains. Most of these were Southeastern states. This group included:

Alabama: up 150%

Wisconsin: up 84%

Georgia: up 71%

Virginia: up 55%

Kentucky: up 52%

Hay disappearance

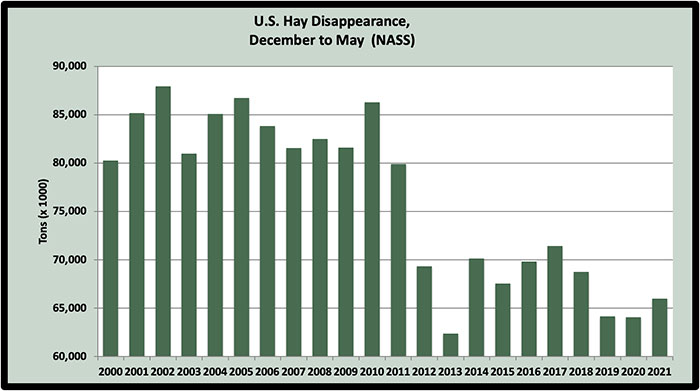

Hay disappearance (primarily feeding) between December 1, 2020, and May 1, 2021, totaled just over 66 million tons. This was about 2 million tons higher than the past two years (see graph).

A new normal has developed in terms of hay that moves out of the barn from December to May.

Prior to 2012, disappearance from hay barns was always in the 80 to 85 million tons range. Since 2012, it’s been rare to have a year where disappearance exceeded 70 million tons. During the past three years, hay feeding has been under 67 million tons. In other words, about 10 to 15 million fewer tons are being consumed from December through May, and that’s been occurring for the past 10 years.

Moving forward

So, where does this leave us from a hay market perspective in the short to mid-term?

What we know is that hay prices in most regions are currently at least $10 to $15 per ton higher than one year ago. That matches up with the lower May 1 hay stocks. In some states such as California, hay prices are $25 to $30 per ton higher than a year ago.

Drought currently looms heavy or already exists in many U.S. regions. This situation could improve or get worse and will ultimately have a big impact on the direction of hay prices.

Historically high commodity prices also provide reason for stronger hay prices in 2021. Many livestock feeders will look to good-quality hay to replace energy and protein previously supplied by corn and soybeans. Milk prices are projected to improve in 2021, but some of that income will be offset by higher feed prices.

Export volumes during the first quarter of the year have been slightly better than 2020. This will help set the tone for prices in the West.

It’s reasonable to expect that hay prices in 2021 will revert to 2019 levels or higher. There are few indicators that point to weaker prices, although a strong hay production year might temper the upside.

Finally, let’s not forget the two hay market mantras that hold true every year. First, high-quality hay always sells for a premium price and costs no more to make than poor-quality hay.

Second, hay markets are first and foremost a regional phenomenon. Local weather conditions and predominant enterprise types (dairy, beef, or equine) will ultimately dictate the demand and price of hay.