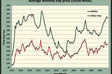

One year ago, alfalfa hay prices were in an epic stall pattern dating back to mid-2019. The average price for alfalfa hay (all qualities) essentially hovered in the $170 to $180 per ton range for month after month.

That situation rapidly changed during 2021 when average alfalfa hay prices soared from $171 per ton in January to $213 in October. The price of alfalfa hay increased every month through October, the last reported month as of this writing. The average price of Supreme or Premium alfalfa hay was nearly $250 (plus trucking) in October.

The value of hay in 2021 was impressive (unless you’re a buyer), but what was more surprising was the persistent climb throughout the year. Almost always, hay prices peak in April or May and then decline. September and October 2021 had record-high prices for those months, even higher than the drought year of 2012.

So, what will shape hay markets in 2022 and where will we see prices head?

First, let’s acknowledge that weather plays a big role and is always capable of throwing hay markets into a frenzy, as it did in 2021, or it can simply flood the market with hay. Although weather can’t be predicted long-term, we can check in on those factors that we do know and evaluate how they might impact hay prices in the coming year.

December stocks:

USDA will report its December 1 hay stocks tally on January 12. What we do know is that May 1 stocks took a 12% dive earlier this year, and it would seem logical that this year’s December hay inventories will do the same. Last year’s December 1 stocks were down just marginally from 2019.

In 2021, there was a wide range of conditions across the United States. A large chunk of the West and Northern Plains was embroiled in drought, which both hurt the current year’s production and had ranchers feeding hay to supplement parched pastures. There was also a lot of cattle sell-off.

East of the Mississippi River, there were both dry and wet periods throughout the growing season, but hay production was mostly adequate to meet livestock needs.

In many areas, snow was late arriving or has yet to arrive, allowing for an extended grazing season and the conservation of hay inventories.

December 1 stocks offer a good starting point of how well the market will be buffered by any negative production factors in 2022. It’s likely that the January 12 report will depict a picture of high variability between regions, with the West and Northern Plains experiencing the worst cases of empty barn syndrome.

The stocks report doesn’t differentiate based on forage quality. Even in years when stocks are strong, Supreme and Premium quality can remain in short supply.

Acres:

In 2021, forecasted alfalfa production stands at about 47.8 million tons, which is down 10% from 2020. If true, this will surely point to a lower December 1 stocks estimate and support stronger hay prices well into the 2022 cropping year.

Mostly because of drought, some huge alfalfa production declines are estimated for the Northern Plains. South Dakota is expected to be down 51% while North Dakota nearly matches that shortfall with a 49% reduction. Montana’s alfalfa production is expected to drop 38%.

Alfalfa acres and average yield in the U.S. will both be below 2020 levels, according to USDA. The same is forecasted for other hay (mostly grass).

USDA’s Annual Crop Production report on January 12 will offer a final number on harvested hay acres as well as production. We’ll also need to watch planting intentions for next spring.

Exports:

Despite logistic and transportation challenges this year, data from the U.S. Census Bureau indicates alfalfa hay exports in 2021 to all trade partners through October totaled over 2.4 million metric tons (MT). That’s up nearly 7% compared to 2020 and 8.5% above 2019.

All of our alfalfa export growth can be traced to China, easily our top trade partner. Through October, China had imported 1,323,651 MT of U.S. alfalfa, or 55% of the U.S. export total to all countries. Compared to 2020, alfalfa hay exports to China were up 36%. Nearly all of this high-quality alfalfa goes to support China’s growing dairy industry.

For hay other than alfalfa, U.S. exports were up about 5% through October. Japan is the leading importer of U.S. grass hay, purchasing 699,485 MT during that time frame.

Though exports make up less than 5% of the total U.S. production, that percentage is nearly four times higher when only the Western states are considered. Further, it wasn’t too long ago that the percentage of U.S. alfalfa hay exported was only 1.5%.

The export market is a key competitor with domestic markets, especially in the West. It also acts as a destination for hay that would otherwise have to find a home in the U.S. or wouldn’t be produced at all. Assuming China remains a strong trade partner, alfalfa exports will continue to help buoy hay prices, especially in the West.

Dairy:

The outlook for strong milk prices in 2022 is as good as it’s been in at least a half dozen years. From May to November, the nation’s dairy herd shrunk by 122,000 milking cows while demand has stayed strong and dairy export totals continue to obliterate annual records.

Some market analysts are projecting a U.S. average All-Milk price exceeding $22 per hundredweight in 2022. A chunk of this extra income will be offset by higher feed and other input costs. Dairy is a major hay customer, and many dairies purchase all of their baled hay inventory.

Beef:

The U.S. beef cow herd checked in at 31.4 million on July 1, 2021, which was 650,000 head fewer than one year earlier. That decline no doubt escalated as drought conditions in the West persisted through most of the summer. Heifer slaughter in 2021 was the highest since 2011.

Like dairy, market analysts are bullish on beef prices going into 2022 and beyond. However, a smaller beef herd also means fewer cows and calves consuming hay. Beef exports are up about 17% from one year ago and overall demand remains strong. Once again, input and feed costs will eat into profit margins.

Grains:

Corn and soybeans prices remain strong, along with other related by-product feeds. This makes both energy and protein a more expensive feed ingredient and allows hay to compete favorably as a ration ingredient. Higher grain prices, if they hold, may also drive some existing hay acreage to be converted to other commodity crops.

Crop inputs:

Market price drivers aside, another factor that will certainly support higher hay prices in 2022 is the escalated cost to establish, grow, and harvest a hay crop. Forage producers will have to demand higher prices simply to cover their cost of production as it relates to seed, fertilizer, chemical, and fuel inputs.

It’s always difficult to know for sure if input costs are driven by real market production (or logistics) factors or if manufacturers are simply after a piece of the higher farm gate prices for commodities. It seems that high input costs are always strongly correlated to high commodity prices.

What does it all mean?

A case for higher hay stronger prices in 2022 can be found in shrinking alfalfa acres and production, strong beef and milk prices, an improving hay export market, rising input costs, continuing drought, higher grain prices, and an always persistent horse population. Offsetting these positive factors are a smaller number of dairy and beef cows (lower demand) and perhaps shrinking profit margins in the livestock sector from higher input costs.

What won’t change in 2022 is that hay markets are strongly localized, and the supply-demand situation varies from one area to another.

Another foundational hay market force is that high-quality forage brings a premium price, and high-yielding forage carries the best profit margin. Combine the two and you’ll nearly always finish with a healthy bottom line, even with higher input costs.