The cow-calf industry will always be close to my heart. There’s something charming about watching cattle out in the pasture, and to me, it just feels like where cattle ought to be. Cattle spend much of their life eating grass, so high-quality forage in beef systems is incredibly important.

I’ve recently developed a deeper appreciation for forage resources across the Southern states after finishing my master’s program at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and becoming an agriculture and natural resources agent for Louisiana State University. When I started my job in 2023, I was mentally prepared for monsoons and hurricanes. Instead, I walked into the hottest, driest summer anyone in the area can remember.

The drought has taken a major toll on crop production, and everyone from sugarcane farmers to cattle ranchers are feeling the effects. One of the biggest concerns is a lack of hay. Although the dry conditions made for great baling weather, yields have been negatively impacted. In fact, most producers I’ve spoken to declared a nearly 50% yield loss on their typical hay production last year, and they are utilizing bales of rice straw and cornstalks as a supplemental feed source for cattle.

Now, more than ever, testing hay and knowing forage quality is critical. To incentivize producers to test their hay, the Louisiana State University AgCenter hosted their annual forage quality contest in conjunction with the state fair in Shreveport, La. Of the hay samples submitted, two producers from the Vermilion Parish excelled: Bryan Simon and Raymond Fontenot.

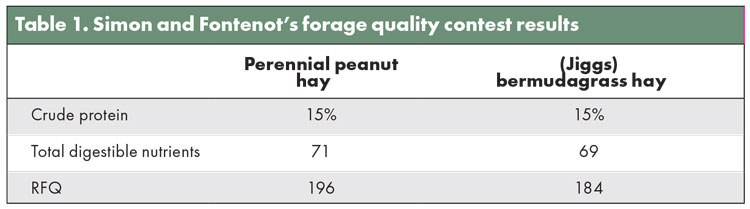

Simon won the legume hay category and was the overall grand champion for the contest, while Fontenot won the warm-season perennial grass hay category. The forage quality results of their hay from the contest can be seen in Table 1.

High-quality grass hay

Fontenot owns and operates Crescent Bar F LLC, which is a grass-fed cattle operation in Meaux, La. He places emphasis on intensive grazing management to produce high-quality, grass-fed beef that he sells directly to consumers. Fontenot values transparency and encourages his customers to ask questions to get to know where their beef comes from. He schedules the dynamics of his operation around the rebreeding and calving seasons while cows are turned out on ryegrass.

“My goal is to use hay as a supplement feedstuff to get through the winter because I usually have good ryegrass for grazing,” Fontenot said. “The reason I started making hay was because I couldn’t get access to the quality of hay I needed for grass-finishing cattle.”

Fontenot routinely tests his hay and uses the results to decide which cuttings he will feed to specific classes of cattle. For example, his first two cuttings are usually his highest quality, so he uses this feed for weaned calves, new bulls, and finishing grass-fed beef. His hayfields are dominated by warm-season perennials like bermudagrass and bahiagrass, and he also overseeds clover.

“The quality is off the scale,” Fontenot stated about his first cutting of the year, which typically occurs sometime in March, weather permitting. Then once he gets started cutting in early spring, he keeps the ball rolling through the summer.

“I usually cut hay late in the day — or even at night — and after baling I immediately put it in the barn,” Fontenot said. “Then once [the regrowth] greens up, I add balanced fertilizer. If the weather conditions are good, I add straight nitrogen two weeks later to really kick it in gear, and that helps the quality.”

He aims to harvest forage every 30 to 45 days. Louisiana typically has tropical conditions and an average rainfall total of 60 inches a year, so both Fontenot and Simon adjust their harvest windows according to the weather.

Top perennial peanut hay

Simon is a second-generation sugarcane farmer who began making perennial peanut hay 12 years ago. At the time, the state of Georgia was having a hard time getting producers to grow perennial peanut, so some companies offered seed to farmers in southern Louisiana. Simon took them up on the offer.

“I got to be friends with the peanut consultant from Georgia, and he mentioned peanut hay to me,” Simon said.

From there, his journey with perennial peanut hay has been a lot of trial and error. He originally planted it with the intent to sell high-quality hay comparable to alfalfa to local racehorse operations, but now he has customers from all kinds of operations.

“About one-third goes to horse stables in the area that have show horses or teach lessons,” Simon said, “Another one-third goes to goats (and sheep) from in and out of the state, as well as dairy cattle and show goats.”

Simon’s perennial peanut hay business has mostly spread through word of mouth. It started with a close relationship with a Katahdin sheep breeder named Mark Dennis who bought his hay. “Every time someone got a lamb from him, they called him about the hay,” Simon said.

He typically gets two cuttings a year, with first cutting at the end of May and second cutting in July. Perennial peanut hay is fragile, and like alfalfa, most of the nutrient content for cattle is in the leaves.

“You have to handle it very gently,” Simon explained, “You have to fluff it at an idle.”

Simon said he has learned a lot in the dozen years since he started making perennial peanut hay. Both he and Fontenot have focused on the craft of hay management, and they prioritize their forage quality. Like these producers, I encourage you to test your hay so you can strategically feed livestock through the winter. Above all, remember that practices such as fertilization and more frequent harvests are likely to reduce supplementation and overall feed costs. •

This article appeared in the January 2024 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 12-13.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.