Winter cereal grains have taken big strides in the forage world as prominent components of double crop systems. In addition to keeping living roots in the soil and covering the ground during colder months, winter cereals have also gained footing in cattle feeding programs.

Winter wheat, winter rye, and winter triticale can be seeded in the fall to function solely as cover crops or outlets for spring manure spreading, but the yield and quality potential of these species also puts them in a favorable position to be harvested for forage. Planting date, maturity at harvest, and weather conditions will ultimately determine how successful winter cereals will be, but a more intensive approach to nutrient management is also necessary to guarantee greater productivity.

In the latest issue of the Crop Soil News newsletter, Tom Kilcer explains how planting date and maturity at harvest impact forage yield and quality of winter cereals. In general, Kilcer says the sooner these species were planted in the fall, the sooner they will resume growing in the spring and the better yields will be. To optimize high yields and high quality, he recommends harvesting winter cereals at or shortly after flag leaf stage, or Stage 9 of maturity, weather permitting.

“Stage 8 does not have higher quality than Stage 9, but you can have a 35% yield reduction from harvesting too soon,” the certified crop adviser asserts. “Conversely, if it is at Stage 8 and you have a sunny day but a week of rain forecasted, get it cut so you have quality forage,” he adds.

Fiber digestibility will plummet once seedheads emerge, which is why Kilcer says keen field scouting is critical. He suggests finding some flexibility in a harvest schedule by seeding a range of early- and late-maturing varieties of winter cereals so not all stands reach flag leaf stage at the same time.

Before harvest occurs, though, proper fertilization will be key to reach yield and quality goals. Kilcer states triticale can require up to 260 pounds of nitrogen per acre to fully prosper in places like New York; however, optimal fertilizer rates will vary from farm to farm and can depend on factors like geographical region, soil conditions, and previous nutrient management practices.

A wide range of responses

John Jones with the University of Wisconsin-Madison demonstrated how these factors impact winter cereals on a recent Focus on Forage webinar. Jones shared results from an ongoing study evaluating spring applied nitrogen response in cereal rye and triticale planted on several sites across the Badger State.

Jones noted alfalfa acreage in Wisconsin has been on a steady descent for the past three decades, falling roughly 40,000 acres per year, and acres planted to corn for silage have remained relatively stable. With that said, planting winter cereals for forage has gained popularity for their high yield and quality potential.

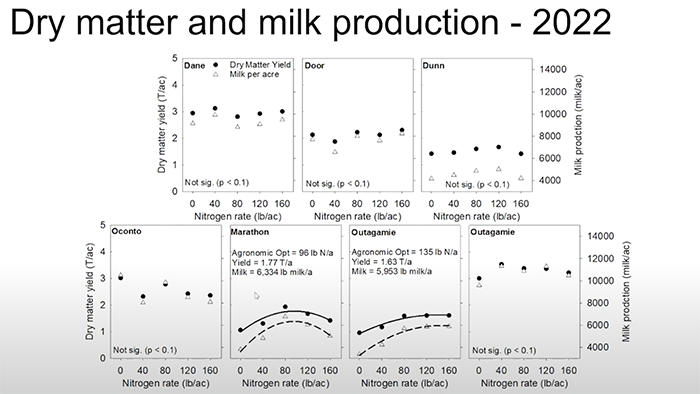

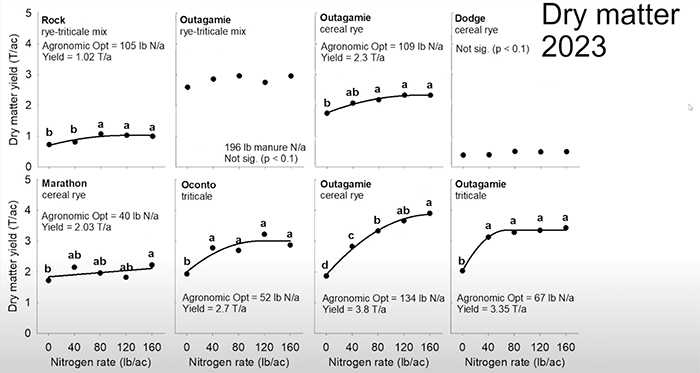

The objective of the study is to evaluate how forage yield responds to zero to 160 pounds of applied nitrogen per acre under different soil and weather conditions. So far, the study includes forage yield and quality data from seven farms in 2022 and eight farms in 2023 that planted cereal rye, triticale, or a combination of the two.

In 2022, only two of the seven sites showed a yield response to added nitrogen. The optimal application rates for both locations were 96 and 135 pounds of nitrogen per acre, which Jones said was rather high considering the respective forage yields of 1.77 and 1.64 tons per acre.

“The optimal nitrogen rates were relatively high compared to the current UW recommendations around 40 pounds of nitrogen per acre,” Jones added. “The yield levels were quite wide in range across the state.”

The narrative flipped in 2023 when all but two locations showed a response to nitrogen, and the optimal application rates for these fields were between 40 and 134 pounds of nitrogen per acre. Jones pointed out that manure was applied on one of the unresponsive stands, and cereal rye at the other site was planted too late for sufficient spring growth.

“In general, we saw some plateaus, or points where the dry matter yield response to nitrogen started to level off,” Jones noted. “One important thing to show is that all the sites showed a significant difference in the fertilized treatments compared to when zero nitrogen was applied.”

Don’t rely on the average

Despite the data, Jones said there is too much uncertainty associated with soil conditions, weather, and forage management to determine general fertilizer recommendations for cereal rye and triticale. For example, the precipitation patterns and soil nitrate concentrations in 2023 caused more prominent yield responses to nitrogen fertilizer, but these factors can change from one growing season to the next.

“There is more site and year-to-year variability than what I would be comfortable with to say the average of all of this data makes sense for every farm that is growing these types of forages,” Jones asserted.

Other quality metrics observed in the study include crude protein levels, neutral detergent fiber digestibility (NDFD30), and milk production per acre. In both 2022 and 2023, crude protein levels improved proportionally with greater nitrogen rates, whereas NDFD30 showed little to no association with fertilizer applications. Overall, milk production per acre correlated with dry matter yield and hit optimal levels with 40 to 80 pounds of nitrogen applied per acre.

Jones suggested producers take a preplant soil nitrate test and consider previous manure practices to guide nitrogen application rates. In general, a higher nitrate test and/or recent manure applications will likely allow for lower nitrogen fertilizer rates without compromising crop yield. Overall, he encouraged producers to invest in more intensive nutrient management of winter cereals to enhance their role in on-farm feed production.