The author owns and operates a forage consulting business, Forage Innovations LLC, in Bay City, Wis.

Alfalfa has been termed the “Queen of Forages.” Unfortunately, her highness is a fickle ruler. Harvesting her wares and maintaining optimal quality requires precise attention from her subjects. Ignore her requirement for a correct and uniform moisture at harvest and the likelihood of a clostridial fermentation is high, which results in the spewing out of butyric acid, biogenic amines, and putrid odors.

The queen’s ideal moisture requirement often converges with Mother Nature’s tendency to be a bit cranky heading into harvest time. Additionally, the two ladies’ obstinate natures seem to coincide when nutrient parameters are optimal. In the heat of the moment, it may seem easier to risk the queen’s wrath and the possibility of a poor fermentation. However, optimal nutrient parameters and digestibility coupled with an undesirable fermentation still equals poor forage quality and disappointing animal performance.

A dearth of sugar

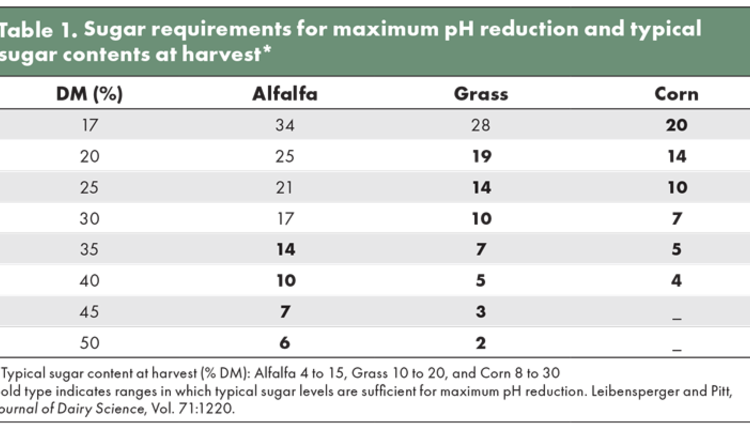

Clostridial spores require two conditions to grow and thrive in alfalfa: high moisture and high pH. While high moisture is implicated as the culprit for clostridial fermentations, these fermentations ultimately occur due to a lack of sugar and the failure to reach an effectively low pH endpoint. Table 1 shows both typical sugar contents of different forage crops and the amount of sugar these crops require at different moistures to reach a pH endpoint. The numbers in bold indicate when enough sugar should be present to attain adequate fermentation.

For alfalfa, note that when the dry matter is below 35%, or moisture is above 65%, there is simply not enough sugar to reach a desirable pH endpoint. Keep in mind that the table is indicative of ideal conditions. Situations where valuable sugar is lost before the crop is ensiled, such as rained on forage (either in the field or pile), delayed fill, or prolonged wilting time, will lower the actual moisture concentration when clostridial activity occurs.

The addition of large numbers of undesirable microbes can overwhelm the fermentation and include such events as manure application on the growing crop or excessive soil contamination. Another complicating factor pertaining to bunkers and piles is they often remain open during harvest until physically covered and sealed with plastic and tires, exacerbating the problem. This contrasts with bagging or upright silos where some sealing occurs during fill.

A point person is needed

Systems, particularly those involving biology, are complicated. A key outcome has emerged on farms that are successful versus those that struggle with desirable alfalfa fermentations. The successful farms have a designated person to monitor moisture. This individual must be dedicated to determining the moisture concentration of the fresh crop and serve as the point person on swath merging and chopping decisions. Often this individual is the herd manager or farm owner because they are most affected by mediocre quality forage and the resulting subpar animal performance.

The order fields are cut is not necessarily the order fields should be merged or harvested due to field moisture differences. Merging often slows or stops the forage drying rate. Below is a protocol that offers the key steps needed to help ensure optimal forage quality and animal performance are achieved.

- Designate one person to be responsible for determining forage moistures and the field order of merging and harvesting. This person is also responsible for monitoring the incoming truckloads of forage to ensure target moisture concentrations are being met.

- Cut mowed alfalfa into small pieces and dry it to determine moisture with a Koester tester or equivalent.

- Order fields for harvesting with a focus on potentially higher moisture spots. Think heavier alfalfa growth, shaded areas, low spots, and pure alfalfa stands.

- The ideal harvest moisture is between 53% and 63%. At these levels, commence merging to slow or stop further moisture loss.

Make it a priority

A second protocol is needed when alfalfa moisture is above the ideal range but harvest needs to commence. In such situations, implement these steps:

- Use a proven anti-clostridial inoculant.

- If alfalfa is above 65% moisture, a separate pile is advisable. Do not mix excessively wet forage with ideal forage.

- Fill the pile quickly and pack well.

- Cover and seal immediately. Sealing needs to happen the day of harvest to conserve sugar content.

- Allow alfalfa to ferment for two weeks prior to opening.

- Feed as soon as possible, ideally within two months.

- Keep the feedout rate as high as possible. Ideally, a foot or more.

In general, if these steps are implemented and the situation isn’t extreme, wet forage can be fed before it turns clostridial. A key part of the above system is to cover and seal the forage immediately to conserve valuable sugar for acid production and encourage a drop in pH. Not sealing and letting the forage properly ferment is akin to piling green chop on the ground and hoping for the best. It will spoil and turn into compost.

Even with careful implementation of the rescue protocol there is risk of fermentation failure. Heavily rained on crops, hay that is already merged and rained on, excessive field drying time, and forage laid in heavy, narrow windrows all contribute to sugar loss. Another notable exception is alfalfa that has excessive soil or manure contamination, which can overwhelm the forage with clostridial organisms.

Manure applications on alfalfa are often cited as a necessity on farms. If manure needs to be applied to growing alfalfa, research suggests applying it immediately after harvest — prior to any green-up — to reduce clostridial fermentation risk on the subsequent crop.

Appeasing royalty can be difficult. A multitude of biological factors that defy control add to the hardship. However, strategic planning, proper decision making, and careful implementation of protocols prior to and during the harvest can significantly enhance the odds of success.

This article appeared in the July XL 2024 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 14-15.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.