Hay exports have taken a noticeable hit in recent years and struggle to rebound to desirable levels. So far in 2025, a combination of economic pressures has negatively impacted the volume of hay that has left the country. Though less of a factor for hay production in Eastern states, the export market has a significant influence on Western hay prices.

As of this writing, the most recent data from USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service shows U.S. hay exports during April. All hay exports that month totaled 223,114 metric tons (MT), which was down 31% year-over-year. Alfalfa hay exports totaled 141,441 MT, representing a 37% decline compared to April 2024. All other hay exports (mostly grass) totaled 81,673 MT — 16% less than April 2024.

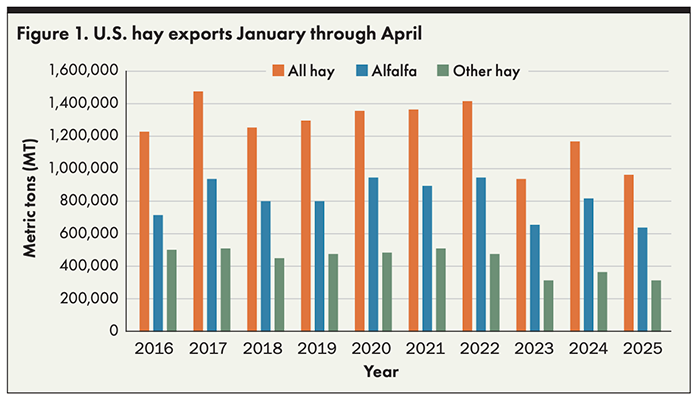

All hay exports from January to April totaled 976,927 MT, which was down 17% compared to the same time frame last year. Although this is roughly on par with export data from 2023, it is a sizable step down in export totals during the first four months of the year compared to most years within the past decade (Figure 1).

Fading demand from China

According to Josh Callen, author of the Hoyt Report, there are three primary factors for the decline in U.S. hay demand so far this year: the trade war with China, dwindling demand from our largest hay customers, and the continuing strength of the U.S. dollar.

China has been the long-time top export market for U.S. alfalfa hay, comprising the lion’s share of shipments out of our nation’s ports. But when the threat of tariffs and an ensuing trade war arose in March, Callen said both parties got spooked and a lot of product was held back or rerouted to Japan at a discount.

“It’s been tough for exporters,” Callen empathized. “A lot of them are kind of in survival mode as they try to make it through this.”

Then, the U.S. and China reached an agreement to lower tariffs while a more comprehensive agreement was negotiated. At this point, Callen reported there was a mixed bag of reactions from major exporters, with some refusing to ship and others rushing to move product before trade conditions changed. Even so, alfalfa hay exports to China dropped significantly from 82,982 MT in March to 50,397 MT in April. Total hay exports to China, including grass hay, were the lowest monthly totals since July 2023.

These trade issues coupled with a diminishing dairy industry can explain China’s reduced demand for U.S. hay. Callen noted China had overestimated its domestic dairy demand and thus overbuilt its national dairy herd, only to end up downsizing the industry and culling a large number of cows in recent years.

Exchange rate uncertainty

According to Callen, a similar situation is taking shape on Japan’s dairy scene, but not quite to the same extent. Although Japan did surpass China on the leaderboard for the first time in a long time, total hay exports to Japan have recently started to lag.

“Shipments to China over the first four months of the year now trail those to Japan — something that hasn’t occurred in several years,” he wrote in the June 6 Hoyt Report. “At the same time, all hay exports to Japan were down 12% year-over-year.”

One of the main drivers of reduced demand from Japan has been an ongoing battle between the U.S. dollar and the Japanese yen. Callen said the exchange rate was virtually unchanged for years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, the Japanese yen has had significantly less buying power against the U.S. dollar.

Another exchange rate for exporters to be aware of is that between the U.S. and Canadian dollars. As the strength of the dollar for our neighbors to the north continues to soften, Callen said Canada has an edge over the U.S. in the global hay market.

“All trading is done in U.S. dollars, so when [Canada] converts U.S. dollars to Canadian dollars, and if their currency is weaker, it just means they receive more,” Callen explained. “That’s an advantage for [Canada] because they can lower their price for hay, yet they are going to get more money back because of the exchange rate.”

There has been speculation that as demand shifts away from our nation’s largest Asian markets, it will be redirected and spread out across more Middle Eastern countries. This has yet to be the case. Callen noted that freight costs and shipping logistics to the Middle East are much more challenging to navigate compared to sending cargo to China and Japan.

“We’d hope that a lower price would attract more buyers, but so far that hasn’t materialized in the numbers yet,” he said. “I wish the [Middle East] would take more of our hay, but I haven’t really seen that shift.”

This article appeared in the July 2025 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on page 35.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.