Are you feeding hay on the same pasture this winter as you have in the past? Winter hay feeding is a common activity around the country, and your livestock require sufficient energy to withstand the winter chill and cold winds. But, if the same pasture is repeatedly used, the path to the hay ring is likely well worn.

Well-fed livestock ensure the integrity of your farm investment. Certainly, hay feeding is necessary if the grass has stopped growing and there is no forage stockpile available. It’s logical to sacrifice a single pasture for hay feeding to limit damage from livestock trampling over wet soil from frequent winter rains and snow melt. Stockpiling forage for deep-winter grazing was a plan that needed to be developed and implemented in early autumn, so if this plan wasn’t executed, then you’ve likely become accustomed to the daily or weekly feeding of hay.

What gets deposited

There are some soil health implications from repeated hay feeding in the same pasture location. Each ton of hay has a relatively predictable level of energy and nutrients. However, the actual nutritive value of hay can only be determined with a forage analysis, as there are considerable variations in quality depending on species, the season of cutting, and nutrient management.

The energy animals consume from hay is utilized as digestible energy to maintain body condition of mature livestock or to grow body mass in developing animals. However, daily deposits of urine and feces contain another source of energy and nutrients that are potentially recycled and utilized by another set of organisms on your farm — soil fauna and microbes, such as earthworms, beetles, bacteria, and fungi.

If you have to feed hay to 30 head of mature cows for 60 days in the winter, then you would need roughly 78 bales, assuming the bales weigh an average of 800 pounds. That winter feeding cost will probably be $2 per head per day or more, so getting fresh bales out frequently will lead to better feed efficiency. You might be putting out four bales twice a week.

Getting back to the fate of the nutrients in the hay, let’s assume that you feed those 78 bales on the same tenth of an acre in the same pasture all winter. Nutrients that are recycled from hay through livestock will be deposited nearby, leaving a potential enrichment zone in the half-acre around the feeding area. That could include up to 1,860 pounds of nitrogen per acre, 310 pounds of phosphorus per acre, and 1,240 pounds of potassium per acre, as well as a considerable amount of calcium, magnesium, sulfur, and a small amount of various trace elements.

These elements were contained in the hay that you either bought from another farm or harvested from your own farm. Such large nutrient concentrations are not likely to be of the greatest value in this small spot and could be considered a liability in sensitive watersheds or when the hay feeding location is near major water runoff channels.

Uneven nutrients

A conservative estimate of the economic value of just the hay nutrients is $50 per ton, which would translate to a fertilizer input cost of $3,100 per acre in the feeding impact zone. This may be a third of the cost of the hay itself, so there could be substantial value in the residual nutrients from winter hay feeding. Another important economic value that is more difficult to quantify is in the residual energy supplied to soil microorganisms as a result of excrement deposition and fouled hay.

The nutrient and energy values to soil are of far greater benefit when spread out over a larger area and not concentrated in winter hay-feeding zones. This should encourage you to learn more about alternative feeding options, such as fall stockpiling for winter grazing, hay unrolling, or bale grazing.

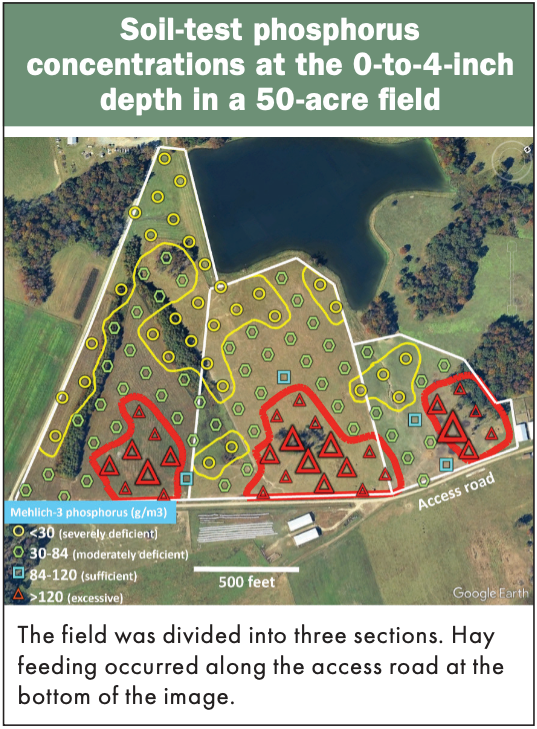

When sampling winter hay-feeding pastures on research stations in North Carolina, researchers, including myself, mapped several hot spots of nutrient concentrations in the top 4 inches of soil — see the figure for an example of soil-test phosphorus on one farm. Hot spots were exactly where repeated winter hay feeding occurred. Fertilizer was not often applied to the remainder of the pasture, which led to nutrient deficiency in the majority of the system. Hot spots had soil-test phosphorus concentrations that were several orders of magnitude greater than sufficient.

A traditional hay-feeding strategy that placed bales on hilltop portions of the pasture near access gates were easier to manage for farm workers. However, this strategy led to excessive phosphorus concentrations in hay-feeding spots and deficient phosphorus concentrations throughout the rest of the system. Results of the full study can be found at bit.ly/HFG-SOS-Jan26.

Do you have similar conditions on your farm? Could hay nutrients be more uniform with a more distributed feeding strategy? The impacts of these alternative feeding options will be explored in future columns.

This article appeared in the January 2026 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on page 9.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.