Hay markets, as with most markets, are fickle and driven by a plethora of related and unrelated forces.

Though it’s our domestic livestock industry and regional weather that ultimately has the most impact on U.S. hay supply, demand, and prices, the western U.S. also deals with the whims and economies of export trade partners.

Last week, Jon Driver, industry analyst for Northwest Farm Credit Services, presented a webinar outlining some of the headwinds and tailwinds influencing current hay market prices. Driver also manages the widely popular Hay Kings Facebook group webpage.

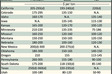

“Hay inventories are down across the U.S. and especially in the West,” Driver said. Citing USDA data, he noted that national hay stocks were down 36 percent year-over-year on May 1.

In the West, Driver noted that California stocks were down 58 percent, Montana was down 43 percent, and Washington stood at 30 percent below last year’s inventory number.

“Even with challenging first-cut weather conditions and reduced quality overall, a low inventory will support higher hay prices,” Driver asserted. “This is particularly true for alfalfa.”

Hay production in California is now about equal to that of Idaho. Golden State hay producers currently harvest the fewest number of alfalfa acres since records started being kept in 1919. “This is a key component for the West Coast export industry and to hay movement,” Driver said.

Hay dynamics changing in the West

As California struggles with fewer alfalfa acres and its dairy producers grapple with low milk prices, more hay is now being exported out of the Northwest ports in Washington than from California.

“The industry is responding to conditions in California. We have seen at least five new hay presses installed in Washington and some existing presses are being updated,” Driver said. “We’re also seeing expansion in Idaho’s hay pressing capacity.”

Driver noted that more lower priced hay from many of the Western states is flowing into California for use on dairies. Oregon, which sits between California and Washington, is shipping hay south to California for domestic use as well as north to Washington for the export market.

“Montana had a long, wet winter,” Driver noted. “This reduced hay inventories as cattle were late getting on pastures, but it also alleviated the drought conditions across much of the state.”

Staying on the drought theme, Driver pointed out that some states such as North Dakota, South Dakota, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Texas are still mired with dry conditions. “Hay tends to flow toward drought,” Driver stated. “We might see more hay moving to these dry areas unless moisture conditions change,” he added.

The analyst also made mention that grass acres were ramping up in many parts of the West. Production of Kleingrass, sudangrass, and bermudagrass are higher in California’s Imperial Valley and the desert Southwest. Northern Idaho is also producing more timothy grass and offers a later maturing alternative to the Columbia Basin’s timothy production.

“So far in 2018, timothy prices are staying strong despite the boost in production acres,” Driver observed.

Positive export growth

The growth in hay export sales has been well-documented, though the first six months of 2018 have not been as robust as 2017. “That’s probably due to lower U.S. hay inventories and higher prices,” Driver opined.

Even with higher export sales, the analyst noted there is new competition coming onto the world market.

“Canada is boosting their hay pressing capacity and is exporting timothy out of British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario,” Driver said. “Countries like Sudan and Pakistan are also expanding their hay production with new hay press and irrigation infrastructure.”

Driver noted that Australia is the West’s biggest export competitor, selling primarily oaten hay that competes with the United States’ grass hay exports. The country has installed four new hay presses in the past five years, giving them a total of eight. However, parts of the country are experiencing drought. This has increased the amount of domestic hay that is staying in the country, while lowering the amount available for export.

Saudi Arabia remains a growing market as their government has virtually eliminated alfalfa production in an effort to conserve water for human food production.

“Like U.S. dairy farmers, the Chinese are also struggling with low milk prices,” Driver noted. This has resulted in consolidation of the industry onto larger farms. At the same time, there has been growing fluid milk demand driven by health-conscious consumers and a growing middle class. Driver thinks both of these trends are positive for U.S. hay export.

Macro headwinds

Driver mentioned a couple of macroeconomic headwinds that are currently occurring, which may temper export sales.

“The rise in interest rates make capital investments more expensive than they were a few years ago,” Driver said. “Also, the stronger dollar relative to other currencies has dropped the buying power of countries looking to purchase U.S. hay,” he added.

Driver pointed out that dairy remains the largest hay customer throughout the West. High hay prices are never favorable for a dairy operation, especially when milk prices are low.

Driver pointed to dairies modifying their cow rations to minimize buying expensive hay. “In some cases, that may mean producing their own hay and buying the grain ration components,” he said. “Nevertheless, improved milk prices would go a long way in boosting demand for domestic hay.”