Little things often lead to big results. That’s always been the case when it comes to pasture and forage production.

At the Arkansas Forage and Grassland Council’s virtual Fall Forage Conference, John Jennings presented some practical tips to help farmers realize more profit from their forage and livestock enterprises. The longtime University of Arkansas extension forage specialist spoke from his experience of interacting with producers, setting up on-farm demonstrations, and from his own research trials.

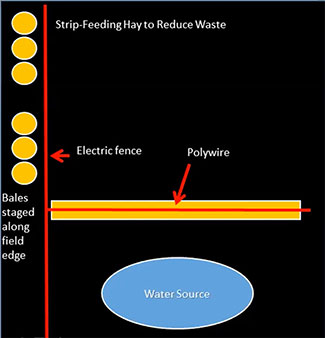

Use wire to reduce feed waste

The first tip provided by Jennings pertained to hay feeding on pastures during winter. Often, when a bale is rolled out to feed, cows trample and waste a lot of the forage.

To minimize this waste, Jennings highlighted a system that he had seen on a beef producer’s farm in Arkansas. The producer staged his round bales in a row behind a strand of polywire. Then, as feed was needed, he would roll out a bale (or several) and run another polywire over the rolled-out hay. This helped eliminate waste and made it easy to allow access to new feed by simply moving the polywire as would be done in a pasture strip grazing system.

Added advantages to this system included spreading out the nutrients provided by the cattle and hay. In addition, cattle were more prone not to congregate in one place, which helped minimize mud creation.

Renovate the mud holes

If you have either sacrifice paddocks or hay-feeding areas that get muddy, Jennings encouraged producers to renovate those areas by leveling out the soil with a drag. Then, spread desirable forage species such as white clover, crabgrass, or bermudagrass over the bare ground.

By putting this practice in place on several farms, Jennings was able to suppress a lot of the weeds that normally germinate and establish in these bare, muddy areas. The seed can be spread with a small hand-crank seeder or with an ATV-mounted spreader.

Be patient

Jennings cautioned to not begin grazing fall-planted annuals too early. “If you put cattle on those fields where the rows are just visible, it’s going to stay that way until spring,” he said. “This really cuts back your yield potential. You really need 8 to 10 inches of growth before allowing cattle on a field. Remember, leaf area is needed to grow more leaf area.”

Spread the ryegrass growth

Nitrogen fertilization is needed for ryegrass planted last fall. In Arkansas, the big production month for ryegrass is April.

“If we get some nitrogen fertilizer out there in February, we can push the green up on the ryegrass earlier and start grazing sooner in March,” the forage specialist explained. “This may not need to be done on every field, but by doing a portion of your fields, you can begin grazing earlier, spread out your production peak, and shorten the hay-feeding period.”

Sod-seeding options

This is the time of year when many producers interseed clover into their existing grass pastures. This can be done by broadcasting and dragging or with use of a no-till drill. In Arkansas, Jennings recommends overseeding into fescue during February and into bermudagrass during October after the warm-season grass goes dormant.

“For this to work the best, grass sod needs to be short, and your soil fertility needs to be at recommended levels,” Jennings said. “It’s important not to place clover seeds too deep, and don’t apply any nitrogen fertilizer or manure where clover is seeded. The added nitrogen will cause existing grass to crowd out the developing seedlings,” he continued.

Jennings has done some research demonstrations looking at strip seeding clover into pastures where clover is seeded at three to four times the normal rate in 50-foot strips while leaving adjoining 150-foot strips unseeded. This intensifies the stand in the seeded strips and cows eventually spread the seed to other areas over time.

His next effort involved what Jennings calls “stripe seeding.” In this case, clover is seeded at three to four times the normal rate in 10-foot strips (one drill pass), and then two or three drill passes (20 or 30 feet) are skipped before doing another seeded stripe. “For fields where you’re having trouble getting clover established, it’s something to think about,” Jennings noted.

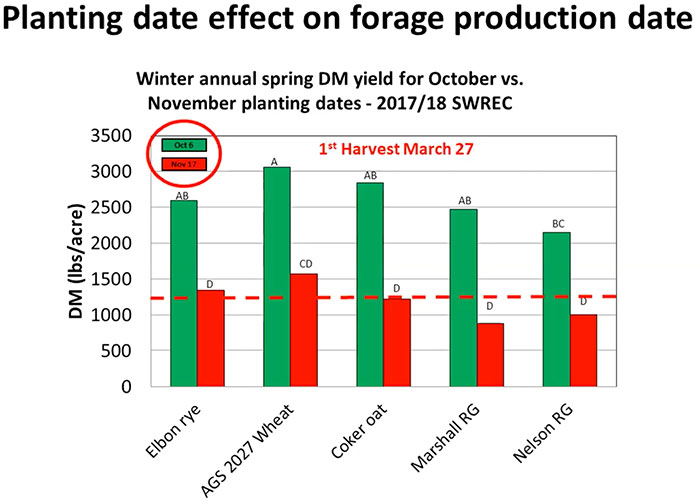

Winter annual planting dates

The forage specialist pointed out that planting date in the fall has a profound impact on spring production. In reviewing some data from 2017 and 2018 where cereal rye, wheat, and oats were planted either on October 6 or November 17, he noted that first harvest yields were significantly better for the earlier planting date (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

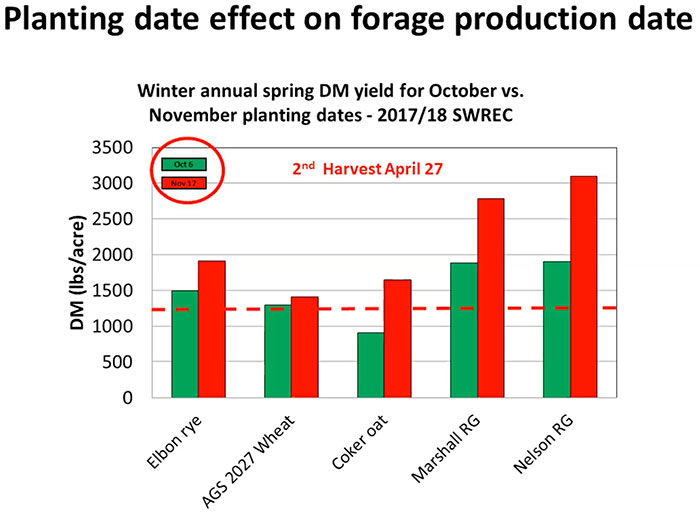

All of the early planted cereals harvested on March 27 yielded 2,500 to 3,000 pounds per acre. For the later planting date, cereal forage yields were 1,500 pounds or lower. Yields for a second harvest taken on April 27 proved to be much lower, although the late-planted cereals yielded more than the early planted ones (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Ryegrass proved to be somewhat of a different story. The early planted plots still yielded the most for the March harvest date (2,000 to 2,500 pounds per acre; see Figure 1). However, the late-planted ryegrass yielded significantly more at the April 27 harvest (2,500 to over 3,000 pounds per acre; see Figure 2).

“These differential yields are not necessarily a bad thing,” Jennings explained. “As you look at a forage program, you could plant some of your annuals early and some of them late to help spread the early season grazing window.”

For those producers who didn’t get as much planted in the fall as they would have liked, Jennings recommends planting either spring or winter oats or ryegrass this spring. “Planting winter cereals in the spring usually results in very low production because of their vernalization requirement,” he said.

Jennings concluded by reminding farmers that forage decisions don’t pay immediate dividends. It usually takes 30 to 60 days for forage practices to show results because forage crops don’t grow or regrow overnight. As a result, he recommends to plan at least one season ahead.