Forage producers differ greatly in their tolerance for weeds that invade hayfields or pastures. In the West, where hay is often grown for retail or export, there is nearly zero tolerance. Conversely, I’ve visited with some producers who seem content to let weeds coexist with their more desirable forages.

In the spectrum of weed tolerance, where is the right place to be?

The answer might depend on whether you are feeding your own forages or marketing them. The type and class of species being fed also comes into play, along with the type of weeds present.

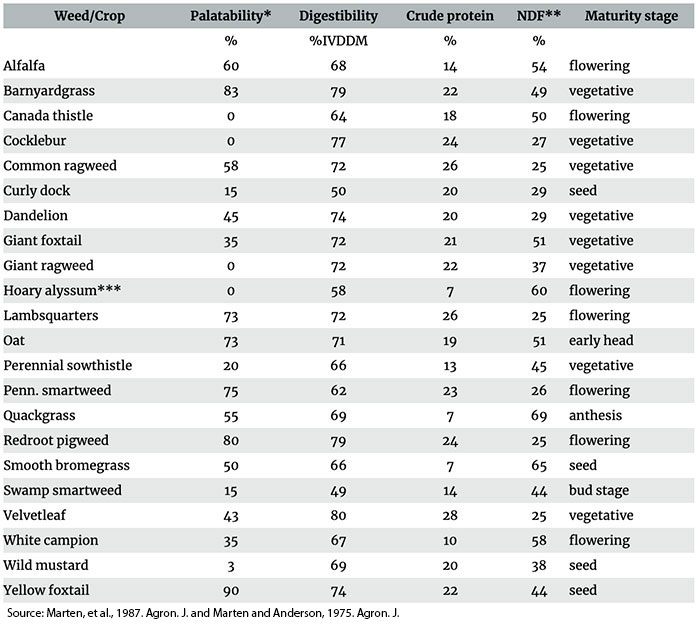

In a recent edition of the Minnesota Crop News, Craig Shaeffer, Krishona Martinson, and Jared Goplen of the University of Minnesota note that both annual and perennial weeds have the potential to provide nutritional value to livestock (see table below). Many of them also thrive in challenging weather conditions such as

drought.

Not all bad

“Pigweeds, lambsquarters, and Canada thistle are high in crude protein and digestibility,” the authors explain. “However, like forages, nutrient content is affected by maturity. Less mature plants have a higher nutritive value than more mature plants.”

The intake potential of weeds by ruminants is best associated with their neutral detergent fiber (NDF) concentration, which limits the volume of forage within the rumen. Lignin also affects the rate of digestion and movement of weedy forage from the rumen.

“Grass weeds like quackgrass and foxtails have higher NDF and lower intake potential than forbs like dandelion,” explain the authors. “Dandelion has low NDF and high intake potential when vegetative, but dandelion flowers reduce its palatability. Quackgrass has a similar nutritive value and intake potential as smooth bromegrass.”

Palatability and forage quality of common annual weeds

Not all good

There are also several good reasons for not allowing weeds to proliferate. Some species contain compounds that drastically impact their taste and palatability. Ragweeds, mustards, cocklebur, and milkweeds are included in this group.

Weed species such as lambsquarters and pigweeds can accumulate high levels of nitrates, especially under drought conditions. “Ensiling will reduce the concentration of nitrates, although the reduction is dependent on the extent of fermentation,” the authors note.

Some morphological traits have an antiquality influence and will reduce forage intake. Characteristics such as hairiness and thorns fall into this category, and they are problems in species such as ragweed, velvetleaf, and Canada thistle. Some weeds with thorns and awns on their seeds can injure the mouths of animals and cause additional health concerns.

What’s being fed?

If a hay or livestock customer doesn’t want to buy weedy forage, then weed tolerance is not an option. However, it is well-documented that ruminant livestock species vary in their ability to tolerate and perhaps thrive on a weedy diet.

The Minnesota forage specialists point out that sheep and cattle are the species most susceptible to nitrate poisoning. Goats are well-known for their ability to consume a diverse diet, including bushes and forbs. On the flip side, horses can be more selective and adversely affected by the consumption of weeds.

Grazing livestock opens the possibility for the consumption of toxic weeds if more palatable and desirable species aren’t present. Overstocking can also put livestock in a position of forcing animals to eat toxic weeds or weeds high in nitrates. Animals can adapt to higher amounts of some antiquality components if forage is introduced slowly into their diet.

“Strategically feeding weedy bales or silage by including them as part of a total mixed ration will allow for smaller amounts of antiquality components to be fed at any time and allows an acclimation period for livestock,” the authors suggest.

Weedy forages can provide value, especially during years when feed inventories are short. However, they need to be fed with caution and only after proper identification to rule out any poisonous plants.