The sun is setting later and later each day, and grazing season is just beyond the horizon. With that said, producers will need to make many decisions before livestock can be put out on pasture, including how to handle the spring flush.

The spring flush is a term used to define the dramatic plant growth seen in cool-season grasses in April and early May. In a webinar by the University of Missouri Extension, Ryan Lock informed producers about managing this surplus of forage to maximize its quality and reduce waste.

“We are trying to balance the forage growth and availability with what the livestock needs are now, plus trying to keep in mind what our future needs might be as far as hay production; this is difficult with unknown growing conditions,” the forage and livestock systems specialist asserted.

Growth factors

Forage growth will commence when soil temperatures rise, pulling perennial pastures out of their dormant state. This will occur when daytime highs reach 50°F to 60°F and nighttime temperatures are at least 40°F for several nights in a row.

In addition to warmer weather, nitrogen fertilizer can also kickstart plant growth and encourage an earlier start to the grazing season. Even so, Lock suggested that applying nitrogen at low rates or to targeted acres may be more cost-effective than administering a blanket application to all acres, especially in early spring.

Lock recommended waiting to turn livestock out to graze until grass is 4- to 6-inches tall, and then rotating them to a new paddock when forage is 2 to 3 inches in height. Continuous grazing can be detrimental to pasture productivity, and allowing animals to overgraze can interfere with regrowth. Plant height must be monitored regularly and can be done by developing a grazing wedge at www.grazingwedge.missouri.edu.

Extra grass

When the spring flush is in full force, Lock advised producers to harvest forage that will not be grazed before it reaches its reproductive stage. To illustrate the benefits of this, researchers at the University of Missouri conducted a study that evaluated how forage quality and animal performance was affected by different management strategies in three grazing systems.

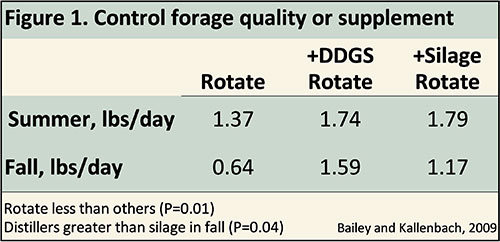

Cattle in the first field were a control group, grazing unmanaged forage that eventually became overmature. Cattle in the second field grazed under similar conditions, but they received 2 to 5 pounds of dry distillers grain per day to supplement their diet when feed quality declined. Cattle in the third field grazed as well, but excess grass in their pasture was harvested to make silage. Data from the study shows forage in the latter treatment provided the highest nutrient levels.

“We got three to four points better in crude protein after the silage was made because the grass was basically in a vegetative state from April 1 to Nov. 1,” Lock explained. “The same advantage occurred for energy.”

These results were reflected in the animals’ average daily gain during the summer. Cattle in the control group gained approximately 1.4 pounds per day, cattle that were supplemented with dry distillers grain gained about 1.7 pounds per day, and cattle in the third treatment where excess pasture was harvested for silage gained roughly 1.8 pounds per day.

In the fall, the average daily gain of cattle in the silage group was surpassed by that of cattle fed dry distillers grains; however, it was nearly two times greater than the average daily gain of animals in the control. Lock predicted simply mowing pastures would elicit a similar response because you’re omitting the fibrous reproductive structures and stimulating vegetative regrowth. Overall, the spring flush is an opportunity to manage pastures in a way that will ensure a steady supply of high-quality forage all year round.

Amber Friedrichsen served as the 2021 Hay & Forage Grower editorial intern. She currently attends Iowa State University where she is majoring in agriculture and life sciences education-communications and agronomy. Friedrichsen grew up on her family’s diversified crop and livestock farm near Clinton, Iowa.