The problem at Virginia Tech’s McCormick Farm in the Shenandoah Valley was not dissimilar to what many cow-calf operators face — too much feeding of hay and not enough days on pasture.

It seemed reasonable to fall stockpile some of the farm’s toxic tall fescue pastures, but as a result of frequent late summer and fall droughts, there was simply no place to put cows whenever fall stockpiling was attempted.

Former Farm Superintendent David Fiske recognized that there was an overabundance of pasture growth in the spring. This was often made into hay and fed back to the cattle during five months of the year.

In 2008, rather than make all of the excess spring growth into hay, Fiske began stockpiling some of the spring and early summer growth not needed for grazing. This was then used later in the summer while the fall stockpiled forage was allowed to grow.

“Summer stockpiling is a system for enabling fall stockpiling,” explained Matt Booher, an extension agent with Virginia Cooperative Extension in the Shenandoah Valley. He recently explained the McCormick Farm’s summer stockpiling system during a University of Missouri Forage & Livestock Town Hall webinar.

“One acre of good, stockpiled grass can usually provide a cow with one to two months of winter grazing,” Booher said. “This assumes good field productivity, favorable weather, and some form of managed grazing.”

In states like Virginia and Missouri, Booher noted that a practical goal is to limit hay feeding to about 90 days per year, and fall stockpiling pasture for winter grazing is the best tool available to extend the grazing season and reduce feed costs.

Over the years, the Shenandoah Valley research farm has been able to extend its grazing season by about 60 days when using a summer and fall stockpiling system. Currently, cows graze into late January or February, and this has resulted in an estimated feed cost savings of $1.20 to $1.40 per head per day, depending on the year.

Save it for later

Booher explained that Fiske settled on a system where 25% of the pasture acreage is stockpiled during the summer beginning with spring green up. The remaining pasture acreage is then rotationally grazed.

About mid-July, an additional one-third of the summer rotationally grazed acres are set aside to rest. The remaining rotationally grazed acres, comprising 50% of the total acres, are used until mid-August, then they are fertilized and allowed to grow for fall stockpiling.

In mid-August, the cattle are moved to the acres that have yet to be grazed or hayed during the summer — the summer stockpile. These paddocks are strip-grazed to avoid selective consumption.

Booher said no back fence is used on the summer stockpile so that cows can return to a water source. A new strip is offered about every two to three days. At the McCormick Farm, about two months of grazing is realized from the summer stockpile.

Once the summer stockpiled forage is consumed, which is about mid-October, then the cattle are moved to the 25% of the pasture base that’s been resting since mid-July. This acreage provides enough additional forage to support cattle until late November.

Finally, the fall stockpiled forage — 50% of the total pasture acres that has been idle since mid-August — is strip-grazed to maximize utilization. The fall stockpiled forage is grazed into February.

The forage quality of the summer stockpiled forage is better than what might be expected.

In conducting forage tests of the summer stockpiled forage, Booher said it was about 12% crude protein and 60% total digestible nutrients (TDN). Not surprisingly, the total ergot alkaloid concentration was high but no worse than the rotationally grazed summer pastures.

“We’ve found that the summer stockpile is a simple way to extend the grazing season,” Booher concluded. “There is significant cost savings without much additional labor or infrastructure. It also allowed the farm to carry one cow-calf pair on just a little over 2 pasture acres and 0.6 hay acres.”

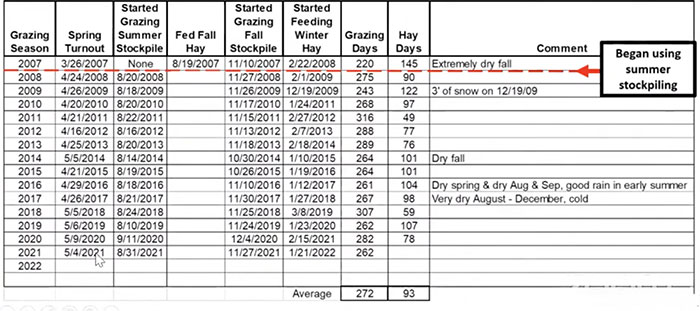

The historical results of the summer stockpile system at the McCormick Farm are outlined in the table below. Booher’s full presentation is available on the University of Missouri’s Forage & Livestock YouTube channel.

Grazing and hay-feeding days at the McCormick Farm