Winter rye is a popular winter annual to plant after corn or soybeans in the Midwest because of its ability to overwinter and acquire nutrients from the soil. In addition to protecting the ground and preventing erosion, this cereal grain can be harvested for hay or grazed in the spring, too.

Like most forages, haying or grazing winter rye is a balancing act between achieving high yields and capturing forage quality. In a recent article from the University of Minnesota, Craig Sheaffer, extension forage agronomist, and Troy Salzer and Nathan Drewitz, extension educators, recommend harvesting winter rye at boot stage to optimize yield and quality.

“Boot stage is just before seedhead emergence when the head can be felt near the top of the last leaf,” the authors explain.

Forage yield typically rises as winter rye matures; however, external factors like weather conditions, latitude, soil fertility, and planting dates can positively or negatively influence potential forage yield. For example, yields may be greater in a field where nitrogen was applied, whereas yields may be lower in a field where winter rye was planted late in the fall.

Forage quality, on the other hand, usually falls over time as protein content and fiber digestibility levels drop. In fact, the relative forage quality (RFQ) of this forage can go from over 150 RFQ during vegetative stages to near 100 RFQ at or just after boot stage. This is primarily because of the growing proportion of stems and inflorescence on plants, which have much more lignin and structural fiber compared to that of leaves.

“Until boot stage, winter rye can be used in rations of growing heifers and lactating cows; however, forage RFQ and energy content decline rapidly after boot stage and it is best suited for maintenance diets, or for use as a fiber source in higher energy diets,” the authors state. “For an accurate measurement of nutritive value, submit samples to a forage testing laboratory.”

Mineral content changes, too

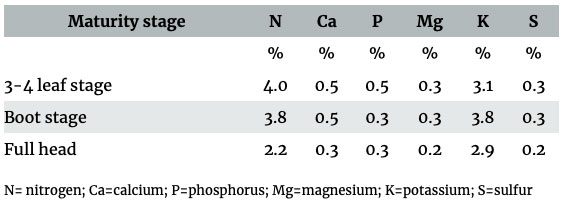

Similar to RFQ and energy, mineral nutrient concentrations tend to taper in plants as winter rye transitions from boot stage to flowering stage as well. Nitrogen and potassium are the most prominent mineral nutrients in plants, and they show the greatest decline in concentration as winter rye matures, too.

Table 1. Forage cereal rye mineral concentrations at several maturity stages.

Although harvesting winter rye sooner in the spring may promise higher nitrogen and potassium content in crops, the latter nutrient can be concerning for lactating dairy cows. Excess potassium in dairy rations may lower calcium levels in animals’ blood plasma at the onset of lactation, also known as hypocalcemia or milk fever.

“Rye is efficient in extracting soil potassium, and as a result, its forage potassium levels can routinely be over 2%. This can predispose cows to milk fever, regardless of the forage calcium level,” the authors assert.

Harvesting winter rye for feed at boot stage might also remove more mineral nutrients from the soil. Nutrient removal is a function of nutrient concentration in the plant and forage yield, and the authors note each ton of winter rye harvested at boot stage could remove up to 76 pounds of nitrogen per acre, 76 pounds of potassium per acre, and 6 pounds of phosphorus per acre.

Amber Friedrichsen served as the 2021 and 2022 Hay & Forage Grower summer editorial intern. She currently attends Iowa State University where she is majoring in agricultural communications and agronomy.