At this time last year, the average price for alfalfa hay (all qualities) had broken through the $200 per ton barrier; in fact; that occurred in mid-2021. It was easy to wonder how much higher hay prices could actually go without buyer resistance.

As it turned out, hay prices could go much higher. From January 2022 to October 2022, the average alfalfa hay price moved from $211 per ton to $281. The previously record-high average price of $227 per ton set in May 2014 was obliterated. Some Supreme and Premium quality hay was selling for over $400 per ton for most of the year.

For the second year in a row, there was no typical April-May price peak for alfalfa hay. The average U.S. price just kept climbing month after month, although moderation was eventually seen in some regions where 2022 production was above average.

So, what will shape hay markets in 2023, and is there still room for upward price movement?

Just as weather played an important role in hay markets during 2022, the same will be true in 2023. Drought or excessive water will surely play a role in some regions, as will water availability in the West. Although weather can’t be predicted long-term, we can check in on those factors that we do know and evaluate how they might impact hay prices in the coming year.

December stocks:

USDA will report its December 1 hay stocks tally on January 12. What we know is that May 1 stocks took a 7% dive earlier this year, and that followed a 12% drop the previous year. Last year’s December 1 stocks were down 6% from 2020 and approached the record-low level set in 2012.

In their October Crop Production report, USDA forecasted alfalfa and grass hay acres to be up in 2022 compared to 2021; however, both yields and total production are expected to be lower, especially for hay acres other than alfalfa.

In 2022, as in most years, there was a wide range of conditions across the United States. Severe drought conditions shifted from the Northern Plains in 2021 to the Southern Plains and western Midwest states in 2022. This significantly impacted hay production in those regions. In both situations, there was a lot of cattle sell-off and hay feeding began earlier than normal.

Irrigation water, or lack thereof, limited hay production in some parts of the West and strategies continue to be developed for Western growers to get the most hay production from limited water supplies. In some cases, water was cut off in 2022.

East of the Mississippi River, there were both dry and wet periods throughout the growing season, but hay production was mostly adequate to meet livestock needs. Haylage inventories in the dairy regions of the Midwest and Northeast also appear to be good.

December 1 stocks offer a good starting point of how well the market will be buffered by any negative production factors in 2023. It’s likely that the January 12 report will depict a picture of high variability between regions, with some Western areas and the Southern Plains experiencing the worst cases of empty shed syndrome.

The stocks report doesn’t differentiate based on forage quality. Even in years when stocks are strong, Supreme and Premium quality can remain in short supply.

Acres:

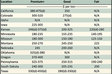

In 2022, forecasted alfalfa production stands at about 48.8 million tons, which is down only 1% from 2021. Last year, October-predicted production was below the final actual production reported in January. If the current USDA forecast holds, alfalfa stocks shouldn’t be much different than the previous year.

Mostly because of drought, some huge alfalfa production declines are estimated for the Southern Plains and some Midwestern states. Missouri is expected to be down 40% while Colorado’s shortfall is predicted at 36%. Texas is off 26%, and Nebraska, Oklahoma, Nevada, and Kansas are expected to have lower alfalfa stocks going into 2023.

The situation is more dire for grass hay. Total U.S. production is expected to drop by 11%. Texas grass hay production is projected to fall over 45% from 2021 while Oklahoma is down 33%.

USDA’s Annual Crop Production report on January 12 will offer a final number on harvested hay acres as well as production. We’ll also need to watch planting intentions for next spring.

Exports:

Hay exports comprise an important component of Western hay markets. Export sales help to set market prices, competing with domestic end users. About 20% of the alfalfa hay produced in the Western coastal states leaves the U.S. That percentage may be on the rise as dairies in states such as California feed less alfalfa. A much higher percentage of grass hay produced in the West is exported.

Logistic and transportation challenges showed some improvement in 2022. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau indicates alfalfa hay exports to all trade partners through October (most recent data) totaled over 2.4 million metric tons (MT), which was about 2% higher than 2021 over the same period.

Through October, China had imported about 1.4 MT of U.S. alfalfa, or 58% of the U.S. export total to all countries. Compared to 2021, alfalfa hay exports to China were up about 7%. Nearly all of this high-quality alfalfa goes to support China’s growing dairy industry.

For hay other than alfalfa, U.S. exports were down about 11% through October. Japan is the leading importer of U.S. grass hay, purchasing 615,335 MT during that time frame. Its import total was down 11% from 2021.

Dairy:

The outlook for strong milk prices in 2022 came to fruition and, for some price metrics, hit all-time highs. For 2023, the outlook is still favorable for dairy farm profits, but not at the pay prices seen in 2022. Market analysts are projecting a U.S. average All-Milk price for the coming year at $22.70 per hundredweight (cwt). That same metric will post at over $25.00 per cwt. for the current year.

From January through November, the nation’s dairy herd grew by 62,000 milking cows while demand has stayed strong and dairy export totals continue to top previous records. Year-over-year milk production has risen in each of the past five months.

A chunk of the extra dairy income realized in 2022 has been offset by higher feed and other input costs. Dairy is a major hay customer, and many dairies purchase all of their baled hay inventory. Those sales are more frequent and easier to make when dairy bottom lines are in the black.

Beef:

The U.S. beef cow herd checked in at 30.4 million on July 1, 2022, which was 750,000 head (2%) fewer than one year earlier. That decline no doubt escalated as drought conditions in the Southern Plains and West persisted through most of the summer. Both beef cow and heifer slaughter numbers are higher than one year ago.

Similar to dairy, market analysts are bullish on beef prices going into 2023 and beyond. However, a smaller beef herd also means fewer cows and calves consuming hay. Beef exports continue to be strong, and overall consumer demand remains good. Once again, input and feed costs will eat into cattle producers’ profit margins.

Grains:

Corn and soybeans prices remain at historically high levels, along with other related by-product feeds. This makes both energy and protein a more expensive feed ingredient and allows hay to compete favorably as a ration ingredient. Higher grain prices, if they hold, may continue to drive some existing hay acreage into other commodity crops. There are some indications that grain prices may begin to moderate or decline.

Crop inputs:

Overall, production inputs will look to remain high in 2023. For haymakers, that means higher costs for chemicals and fertilizers. Recently, fuel prices have come down, but it remains to be seen if that trend holds. Forage producers will have to demand higher prices simply to cover their cost of production, but hay buyers have already danced to that song in 2022, so the shock factor may not be as bad.

It’s always difficult to know for sure if input costs are driven by real market production factors or if manufacturers are simply after a piece of the higher farm gate prices for commodities. It seems that high input costs are always strongly correlated to high commodity prices.

What does it all mean?

Many of the same factors that influenced hay prices in 2022 will still be in the game during 2023.

A case for steady to stronger hay prices in 2023 can be found in shrinking acres and production, relatively high beef and milk prices, a growing dairy herd, a healthy hay export market, high input costs, a lack of water availability in the West, strong grain prices, and an ever-present horse population. Offsetting these positive factors are a smaller number of beef cows (lower demand) and, in some cases, lower profit margins in the livestock sector from higher input costs.

One question remains to be answered: At what point do hay prices become so high that demand falls and less expensive alternatives are sought?

To some degree, we’ve already started to see softening demand from both domestic and foreign hay customers. Standoffs are occurring between buyers and sellers.

Recently, hay prices have started to level off or even decline in places such as the Midwest. Dairy producers are finding more profitable ration ingredients and beef producers are simply setting limits on what they will pay for hay. Retail and horse markets will always be strong for the right kind of hay.

What won’t change in 2023 is that hay markets are strongly localized, and the supply-demand situation will vary from one region to another.

Another foundational hay market force is that high-quality forage brings a premium price, and high-yielding forage carries the best profit margin. Combine the two and you’ll nearly always finish with a healthy bottom line, regardless of market forces.