Before expanding my agricultural canvas as a national magazine editor, I really had little idea how the rest of the nation operated beyond my home Midwest region. Here, we plant, it rains, crops grow, we harvest, it snows, and then we do it all over again. Water is mostly abundant — sometimes too abundant — and growing season temperatures are generally moderate.

I learned rather quickly that agriculture in a large chunk of the western U.S. operates under a set of rules that, like the Midwest, are largely dictated by Mother Nature, but the rules are much different. There is heat, arid conditions, and water has to be sourced from somewhere other than timely growing season rainfalls.

Over generations, millions of acres of bare or desert land have been “reclaimed” and made into productive farmland. This has all been made possible by irrigation water, sourced from either the land’s surface or underground, depending on the location. The infrastructure for moving water to where it is needed has been generations in the making.

Lifeblood of the West

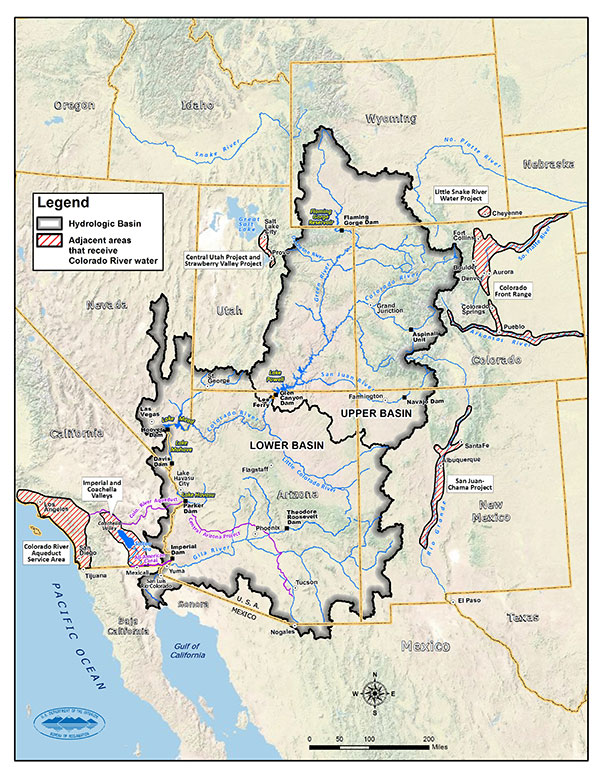

Within Rocky Mountain National Park, west of the Continental Divide, a trickle of water from snowmelt begins to flow and form a national treasure — the Colorado River. That same small trickle of water that began in the Rocky Mountains also flows through the Grand Canyon and eventually makes its way into Mexico.

In some respects, the Colorado River is the lifeblood of the West. Through the years, it has provided irrigation water for millions of acres of crops in portions of seven states — Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California. Further, the river provides water to some major metropolitan areas, including Phoenix, Las Vegas, Denver, Los Angeles, San Diego, and Denver.

Near the Utah–Arizona border is Lake Powell, which is backed up on the Colorado River by Glen Canyon Dam. Further downstream is the Hoover Dam, which forms Lake Mead on the Arizona–Nevada border. Both dams produce hydroelectric power.

For many years, river users were happy. A compact, signed in 1922 between the seven states, dictated water use and abuse. But now there is a problem. A big problem.

Greater water use and less water flow has put the Colorado River System into a state of crisis. Blame it on what you want — drought, climate change, or whatever — but it doesn’t change the fact that there’s simply less water to go around. Both Lake Powell and Lake Mead are in danger of reaching dead pool, the point at which water no longer flows through dams’ outlets. Before that occurs, hydroelectric power generation will cease. Today, if you jump off the end of most boat docks on Lake Powell, you’ll hit solid ground. Plus, you’ll still have a hike to get to water.

Forage at risk

There are no easy fixes for the Colorado River situation. With a slug of contracts, compacts, and treaties governing the waters, few people want to give up what has been rightfully theirs for generations. There’s also the understanding that, in some cases, what doesn’t get used will be lost to somebody else — a “use it or lose it” mentality. If the seven states can’t figure something out pretty quick, expect the federal government to take over.

Politics and interests aside, the fallout of this situation is that millions of acres of forage production are at risk. Alfalfa has become the poster child for water use and is often pointed to by urban interests. But in addition to alfalfa, there are vast acres of pasture and annual forage crops that also have their lifeline hooked to Colorado River water.

A large square footage of the collective U.S. hay barn is filled with forage produced in the Colorado River Basin. You can add to that the cattle and other livestock that are grazed on irrigated pastures in the region and the rural communities whose very existence depends on Colorado River agriculture.

I won’t pretend to have the answers to mitigate the current situation. What I do know is that we’re going to have to learn and use technologies that will get the same (or near the same) production using less water. Those measures are currently being researched heavily and include much more efficient irrigation systems and strategies such as deficit irrigation for alfalfa.

Some of these technologies are not cheap to implement, and that’s probably where the government should step in. They already dole out millions for soil conservation and water quality measures as direct payments to farmers; they can do the same for water conserving measures. That seems to make more sense than simply paying farmers to fallow, which reduces local food production and makes the U.S. more dependent on agricultural imports. A check in the mail or not, farmers want to grow crops, not stare at bare land.