Brock and Heidi Terrell are third-generation beef producers in northwest Nebraska. They don’t need convincing that strip grazing is the way to go when utilizing fall-grown cover crops for lactating cows or growing calves.

The Terrells had started with continuous grazing and eventually went to strip grazing because they saw forage utilization as their weak link.

Through the years, the couple has expanded their cover crop usage and the species they’ve used. Since the 1990s, they’ve seen improvements in soil health, spring weed control, and have been pleased with improved livestock performance.

As one of the participants in recent University of Nebraska Extension research project comparing continuous grazing to strip grazing fall-grown cover crops, the Terrells planted oats and turnips in August.

“I like the grass mixed in with brassica,” Brock said during a recent webinar that focused on the strip grazing study. “The grass slows down digestion for better feed utilization.”

For the continuous grazing, the Terrills’ stocking density was about one cow per acre while strip grazing allowed for 10 to 20 times that number.

“We made weekly moves of about 10 acres each,” Heidi said. “Our exterior fence was electric wire and rebar posts, and polywire and step-in posts were used for the interior fencing. It took me about 20 minutes to set the interior wire for each move. We had two wires set up at a time to have an emergency catch in case there’s a breach of the first wire. No back wire was used so the cattle could get to water,” she added.

Brock explained that the disadvantage of strip grazing is having to routinely set up the fence. But he’s a firm believer that the advantages far out way the disadvantages in that the utilization is so much higher. “Toward the end, the strip-grazed cattle were more content because they were still getting fresh feed every week,” he noted.

When asked how difficult it was to get posts in and out of frozen ground during the winter, Heidi said that she had the best luck with fully metal pigtail posts that can be hammered in. A more expensive but easier tumble wheel fence could also be used. One recommendation offered for removing posts in frozen ground was to twist them first with vice-grip pliers before pulling them out.

Project overview

During the webinar, Mary Drewnoski summarized the results of the strip-grazing project for all the participating farms. The University of Nebraska extension beef specialist explained that most project participants used oats plus turnips or rapeseed. “I like rapeseed because it provides more grazable forage,” she noted.

Most of the project fields were planted in early to mid-August and grazing began in late October to November.

“The forage quality was exceptional in early November, with the mix of oats and brassicas testing 78% total digestible nutrients (TDN) and 23% crude protein (CP),” Drewnoski noted. “It remained high, even after freezing, with a test of 67% TDN and 23% CP in early December.”

Drewnoski prefers about 30% brassica in the cover crop mix, so she typically seeds 50 pounds of oats with 3 pounds of rapeseed per acre.

Across Nebraska, there were eight comparisons made of strip-grazed versus continuously grazed cover crops at five locations. Some locations only had one year of data while others had two. Cattle moves to a new paddock varied from twice per week to one location with a move every three weeks. Five sites used cows and three sites used growing calves.

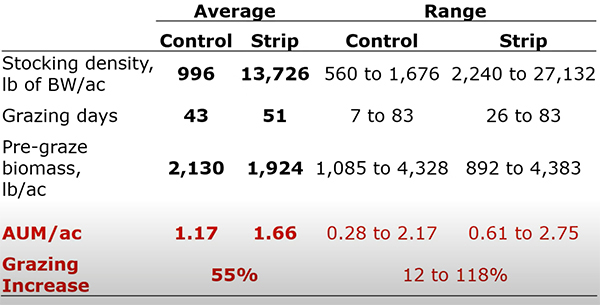

“Across all of the grazing sites, we got a 55% increase in grazing capacity using strip grazing versus continuous grazing,” Drewnoski said. “That number had a huge range over all of the sites, being 12% to 118%. This was probably due to variations with weather,” she added.

Table 1. Comparison of continuous versus strip-grazed cover crop fields

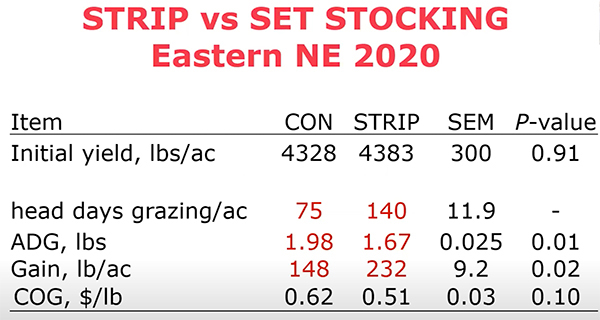

Drewnoski highlighted the results at one eastern Nebraska site using stocker calves. She noted they got 65 more grazing days per acre by strip grazing (Table 2). Although the average daily gain for the strip-grazed calves was slightly lower, the gain per acre was significantly higher, making the cost per pound of gain about 11 cents lower.

Table 2.

Drewnoski concluded by saying that they planned to continue their strip-grazing work with a focus on soil health and using technologies such as virtual fencing.