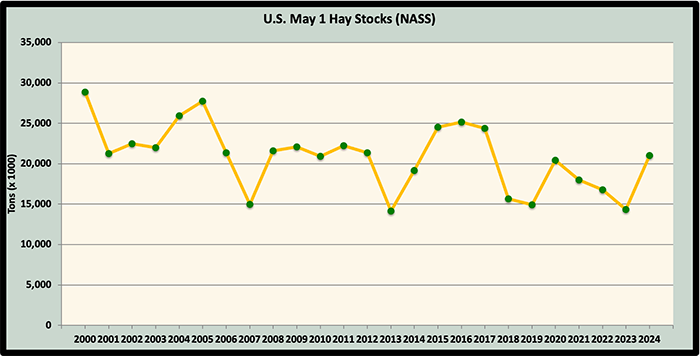

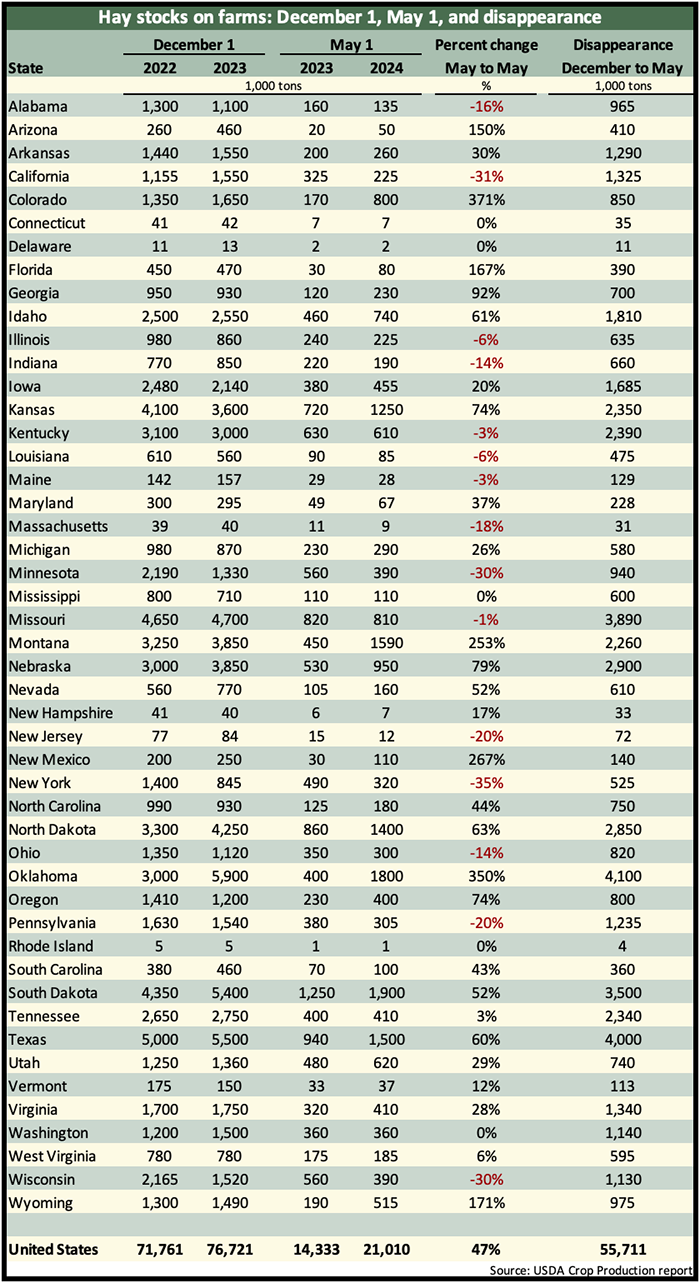

Inventory in U.S. haymows on May 1 jumped 47% from a year ago. Based on USDA’s Crop Production report released last week, May 1 year-over-year hay stocks rose by 6.7 million tons. This follows three consecutive years of May 1 inventory declines.

Hay stocks currently stand at just over 21 million tons. This past December, year-over-year hay stocks jumped by nearly 5 million tons.

The recent May 1 hay stocks estimate is the highest reported since 2017 when the nation’s hay inventory totaled 24.39 million tons.

Some of our largest hay-producing states had significant year-over-year May 1 stock gains (see table below). Those with some of the largest increases include:

Colorado: up 371%

Oklahoma: up 350%

New Mexico: up 267%

Montana: up 253%

Wyoming: up 171%

Florida: up 167%

Arizona: up 150%

Conversely, there were also some major hay-producing states that experienced notable inventory reductions. This group included:

New York: down 35%

California: down 31%

Wisconsin: down 30%

Minnesota: down 30%

Pennsylvania: down 20%

Hay disappearance

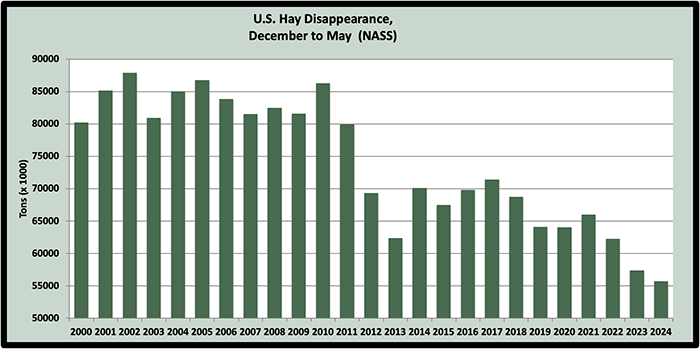

Hay disappearance (primarily feeding) between December 1, 2023, and May 1, 2024, totaled 55.7 million tons. This was about 1.7 million tons lower than the previous year and set a new record low hay disappearance (see graph).

Prior to the 2012 drought year, disappearance from hay barns and stacks was always in the 80 to 85 million tons range. Since 2012, it’s been rare to have a year where disappearance exceeded 70 million tons. During five of the past six years, hay feeding has been under 65 million tons.

Looking ahead

Prior to the release of the May 1 hay stocks report, there was little doubt that U.S. haymows were fuller than the previous year; it was just a question of by how much. A 47% rise is a big number and partially explains the dramatic drop in hay prices over the past year.

Moving forward, weather and water availability will dictate where hay yields and prices head. A La Niña weather pattern is expected to return sometime in 2024, probably later in the growing season.

Moderation from record-high commodity prices makes hay-competitive feeds cheaper. Although beef prices are expected to stay strong in the foreseeable future, milk prices remain down; however, that could change in the latter half of the year. Both dairy and beef herds in the U.S. are down from previous cycle highs and should remain that way in the short term.

Hay crop input prices have gone up substantially in the past two years, but those, too, are starting to subside. Many fertilizer products are down significantly from their previous highs. Still, hay growers will need to be diligent in knowing their costs of production as hay prices moderate.

Hay export volumes during the first quarter of the year are starting to rebound from a woeful 2023. Hence, competition for Western hay may start to improve, especially for high-quality grades.

All totaled, it’s reasonable to expect that 2024 hay prices will remain steady. The free fall in prices has seemed to moderate. At the same time, there is no indication that we will see any significant movement upward unless weather conditions turn negative across a wide swath of the U.S.

Finally, let’s not forget the two hay market mantras that always hold true. First, high-quality hay always sells for a premium price and costs no more to make than poor-quality hay.

Second, hay markets are largely a regional phenomenon. Local weather conditions and predominant enterprise types (dairy, beef, or equine) will ultimately dictate the demand and price for hay.