The author is a professor and extension forage specialist with the University of Kentucky in Lexington.

When I started my forage career back in 1986, directing farmers to a good variety with high-quality seed was easy. I’d simply tell them to “select certified seed of an improved variety.” This would preferably be one with proven performance in replicated, unbiased research trials. Certified seed had the well-known blue tag, which ensured the farmer of the genetic purity of the seed in the bag.

Fast forward to today — you will only find blue tags on a few bags of forage seed in ag supply stores, even among premium products. To understand how to be assured of getting both a good variety and high-quality seed (high germination and purity), we must take a deep dive into seed tags and the seed production process. It’s now more important than ever to read seed tags and understand the quality of the seed being purchased.

The seed tag is a regulated label of the contents of the bag. The Federal Seed Act, in cooperation with state departments of agriculture, provides the regulatory framework for the labeling of seed intended for interstate commerce. Seed tags must contain the following:

Seed kind and variety: Kind refers to the species, and variety is the proprietary name of the genetic material. Seed must be labeled with the variety name, as common or variety not stated (VNS), or variety unknown. Some species may not be required to have a variety name (for example, annual lespedeza in Kentucky).

Lot number: Unique identifying number for a quantity of seed.

Source: The marketer of the seed.

Origin: The specific location where seed was grown.

Germination (%): The percent of seed that will produce viable seedlings under standard conditions.

Hard seed (%): Seed that does not imbibe water during a standard germination test yet is assumed to be viable.

Test date: The date when the seed was tested.

Coating (%): The percentage of the weight of the bag that is seed coating.

End date for viability of inoculum: The last date that preinoculated legume seed is considered to have viable bacteria.

Purity (%): The proportion of the product weight that is seed after accounting for inert matter, coatings, and other crop and weed seed.

Other crop (%): Seeds of other crops found in the bag, such as annual ryegrass in orchardgrass.

Inert material (%): Nonseed matter found in the bag, such as chaff, plant parts, and dirt.

Weed seed (%): Proportion of weed seed in the bag. Noxious weeds must be identified and quantified. They may be classified as prohibited or restricted. Prohibited noxious weed seed may not be found in seed at all. Restricted noxious weeds may be allowable in seed if below regulated levels.

There are federal noxious weeds, and in addition, each state has its own list of prohibited and restricted noxious weed seeds. For example, Kansas restricted noxious weed standards limit the number of buckhorn plantain to 45 seeds per pound, while its alphabetical neighbor, Kentucky, will allow 304 seeds of that species per pound. Kentucky specifies a maximum of 480 noxious weed seeds per pound but also a maximum for each type. Iowa varies the restricted weed seed by the type of forage; fescue may contain up to 80 seeds per pound of dock, but the ryegrass threshold is only 48 seeds.

Some states place upper limits on the percent of restricted noxious weed seed. Indiana, for example, allows a maximum of 0.25% restricted noxious weed seed and 2.5% all weed seed.

What’s in the bag?

The presence of the blue certified seed tag indicates third-party oversight of the seed production process, which ensures it meets high standards for varietal purity. In other words, seed certification assures the producer that the genetics in the bag matches the name on the tag.

Seed certifying agencies like the Oregon Seed Certification Service establish the minimum standards for germination, purity, and other characteristics for certified seed. These agencies also provide third party verification of the seed production process, including things like field history and isolation. The certification process regulates and monitors the seed production process from planting to harvest and beyond. Of course, these added quality control measures add time and expense.

Companies decide whether to certify a seed lot based on demand. For example, in Canada, seed cannot be sold under a variety name unless it’s varietal purity can be documented by third-party oversight, such as with certified seed.

Newer releases are mostly supplied uncertified and are referred to as proprietary or commercial varieties. For these products, companies contract directly with seed growers, supply the seed, and provide oversight of the seed production process. Seed companies have field staff in seed production areas to monitor the production from the growers who have been contracted to raise their proprietary varieties. In this case, the integrity of the originating company is replacing the oversight provided by the seed certifying agency.

Nearly all companies will market some seed in ways other than bags containing a single variety. The most common alternate method of seed marketing is to create a recognizable brand.

Brands are a commercial label whose contents can vary from year to year. You can think of a car model as a type of brand. For example, a Mustang is always a Mustang, but it may change in design from year to year.

A bag of branded seed may contain named varieties (one or many) or VNS seed, either singly or in blend. Sometimes it is just labeled with the species name, with a footnote that it is VNS. A blend is a combination of like kinds of forages (for example, like orchardgrass), and their varieties may or may not be specified.

Blends of VNS seed will have unknown performance and will likely have an attractive price. Better quality blends that contain named varieties allow for better prediction of field performance.

To complicate matters, some blends are marked as a brand, such as the hypothetical “High-Yield Orchardgrass.” These branded blends allow companies flexibility in the specific varieties in the blend each year. Companies choose to market seed under a brand name because they have the flexibility to change the components and still have a recognizable product.

Mixtures are combinations of various kinds of forage. For example, an equine mix in Kentucky might contain orchardgrass, Kentucky bluegrass, timothy, and perennial ryegrass. Again, the better mixes will contain named varieties that allow some prediction of its future field performance.

Choose variety, then quality

For any seed, the variety is the key to its eventual performance in the field. For older varieties like Kentucky 31 tall fescue, the search for quality seed begins with reputable growers supplying seed of the proper genetics. Frankly, this is a weak link in the process because older varieties are without oversight from either a certifying agency or a company. We are left to conclude that when farmers plant older varieties, they are trusting in the integrity of the original grower, the company that distributes the seed, and the local point of sale.

A variety name indicates the genetics in the bag and the seed tag must state the variety for our common forages like alfalfa, red clover, tall fescue, timothy, and orchardgrass or label it “Variety Not Stated.”

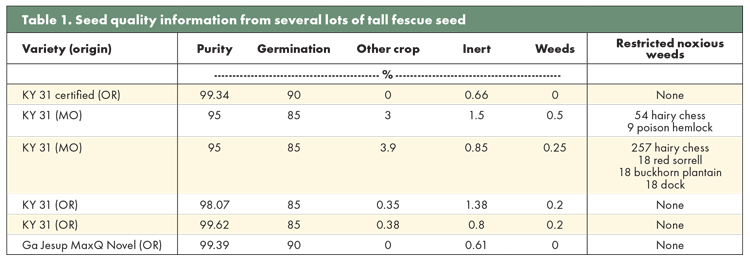

The seed tag can provide insight into whether a seed lot of an older variety is desirable. Table 1 shows the seed quality information from several lots of tall fescue seed, including a certified Kentucky 31 and a certified novel tall fescue variety. All have high purity (95% or greater) and high germination (85% to 90%); however, these seed lots differ significantly in other crop and weed seed. The two Missouri seed lots had detrimental amounts of other crop seed and many more noxious weeds, while the others had low other crop (less than 1%) and no weed seed.

Other crop seed in tall fescue is nearly always annual ryegrass, and levels of 2% and above can be incredibly competitive in new seedings. Noxious weeds like buckhorn plantain and poison hemlock are undesirable in forage seed lots.

Although not shown here, there was little difference in the price per pound of these Kentucky 31 offerings. The higher quality lots of Kentucky 31 were the better buys. Should we really care about the quality of seed in an old and likely toxic endophyte-infected Kentucky 31 tall fescue? The answer is “yes” when there is the simple and better solution of buying a newer commercial or certified variety for essentially the same amount of money.

The point is that people do care. Hundreds of thousands of pounds of Kentucky 31 are sold each year, and buyers have an expectation that the resulting fields will perform true to the variety name. For a grower, that means fields that will withstand abuse, stop erosion, and live forever. Yes, they are likely to be infected, but growers are voting with their pocketbook that they are willing to deal with its limitations.

The bottom line is that we are not going back to the days where everything was blue tagged or sold as common or VNS. Purchasing a better variety means studying replicated, unbiased forage trials for top-performing products and working with a seed dealer and distributor that you trust to get that seed into the back of your pickup truck. Study the labels and look for pure seed with high germination rates and low levels of other crop and weed seed. Secure blends or mixtures where components are named varieties that can be researched. Ultimately, we rely on the integrity of the seed production and supply chain.

This article appeared in the November 2024 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 30-31.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.