“Not all rumors are true, but there is probably a shred of truth in each.” That was Matt Makens’s first comment as he took the stage at the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association’s annual convention last week in Nashville, Tenn. Rumor has it that El Niño is coming back in 2026; however, several things need to fall into place before the warmer, wetter weather pattern officially sets in.

Makens is an atmospheric scientist with Makens Weather LLC based in Colorado. He said historic data and meteorological models suggest 2023 is a prime analog year when forecasting conditions for 2026. So, what happened in 2023?

Three years ago, the sea surface temperatures of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) region of the Pacific Ocean shifted from cool to warm, pushing La Niña out and inviting El Niño in. So far this year, the data show a similar trend.

“For the past several months, we’ve been in a weak La Niña,” Makens said. “That’s driven our dry climate that we’ve had overall.” He added that the biggest impact La Niña will have during the 2025-26 winter likely already happened two weeks ago: extreme cold, ice storms, and dry, powdery snow affecting the eastern half of the country.

La Niña has also left Western states desperate for water. Makens said Colorado currently has the lowest snowpack on record. Drier-than-average conditions persist in Oklahoma, Texas, and across the Southeast. Theoretically, a transition to El Niño causes those drought areas to shrink, and the precipitation pattern should flip from north to south and from east to west.

“Once we flip this, if you’ve been dry, you start to get wet; if you’ve been wet, you start to get dry. That’s the basis of this transition,” Makens said. “What you have got to watch throughout the course of this year will be the strength of this event. A very strong El Niño brings something very different from a weak one.”

A slow shift

The ENSO is in the driver’s seat when it comes to large-scale weather patterns and regional climatic changes. As several pockets of warm water within the ENSO register on the radar, Makens said we are essentially flirting with El Niño. Neutral conditions could set in for now, and the conversation will go back and forth until a steadier warming trend is established.

When that happens and El Niño is confirmed, Makens said the heat energy from surface ocean waters tend to erupt into the atmosphere, increasing the storm frequency along the West Coast and across the South. It’s something to be aware of, but it’s not necessarily urgent, and the speed of the progression from La Niña to El Niño will dictate how widespread and severe that wet weather will be.

“This is not an immediate change,” Makens asserted. “Even if the ocean changes today, it could be two or three months before the atmosphere would respond to it.”

This year will be all about the transition, he continued. The shreds of truth in the rumor about El Niño are proven in historical data that suggests more than a 60% probability of the weather phenomenon setting in later this year. “Every time we run the analogs, those probabilities get higher,” Makens said. “The speed of it is critical. That will drive in water either sooner or later.”

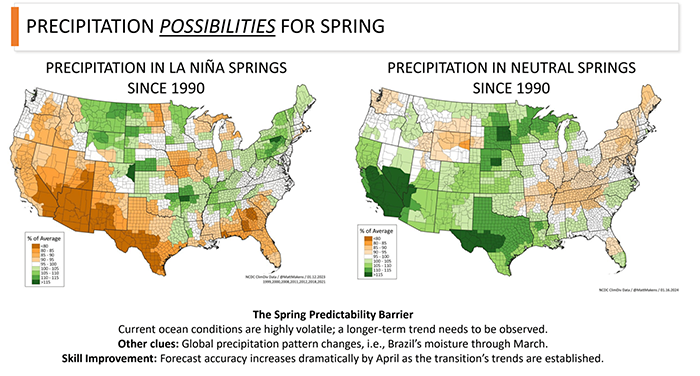

Spring possibilities

Depending on how quickly La Niña exits the scene, Makens said the possible outlooks for this spring include a few extra months of her dry weather or a few months of more neutral conditions. “If we hold onto La Niña for a little bit longer, we are still very dry in the Southwest. If we can get rid of her quickly, you can see where the moisture spreads from the Southwest, through Texas, and all the way to the Upper Midwest,” Makens said

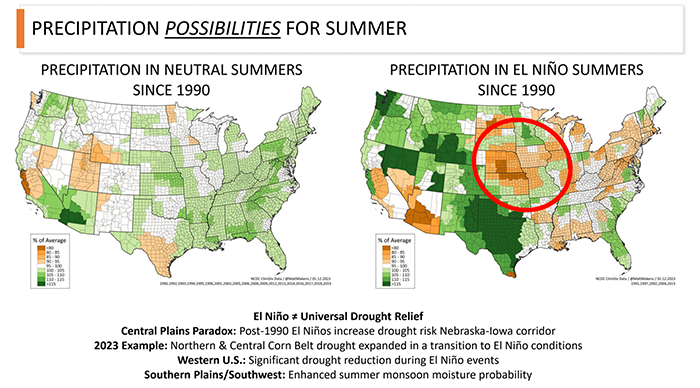

Summer and fall

The summer outlook options include ENSO neutral or El Niño. In the event that El Niño comes running, the Corn Belt is predicted to experience a rapid onset of drought, which was demonstrated in the summer of 2023.

“Caution for the central Midwest — if you ask for an El Niño too soon and you’re worried about corn, that drought can be a concern potentially,” Makens said.

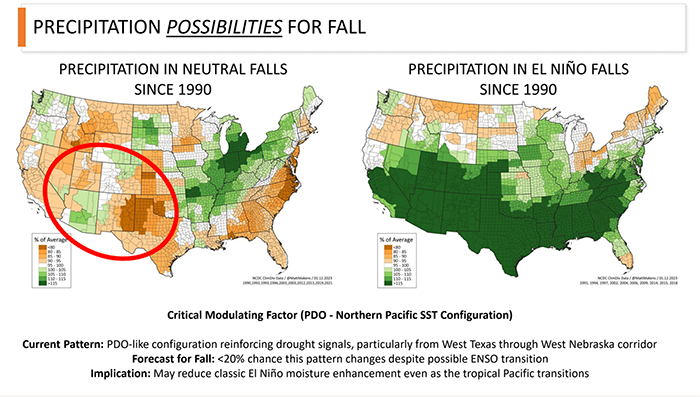

The same options exist for the fall season — ENSO neutral or El Niño. In the latter case, Makens’s weather models suggest a deluge of water for the southern half of the U.S.

Bottom line

Despite El Niño on the horizon, Makens cautioned the audience not to get their hopes up; current conditions will likely persist for the next six weeks as we round out winter.

“If you’re calving, be very diligent in tracking temperatures because we’re not out of the woods. There could be shocks of cold coming out of Canada, and they can be tremendously impactful,” Makens said.

Over time, he expects drought to migrate from the South and Southwest toward the North and Northwest. There may continue to be volatility in air temperatures, but generally speaking, El Niño favors more temperate weather. “Once we pass Easter or so, we are going to start to see the chance of this extreme cold dramatically decrease,” Makens said.

“Moisture will favor the West and the South — that’s what El Niño does,” he added. This is the road map for the year, but Makens emphasized that there are several other factors at play beyond the ENSO that could interfere with his predictions.

“The speed of the transition will be critical. The faster El Niño kicks in, the more drought issues we could have in central corn regions as we spread that moisture out to the West,” he concluded.