Annual ryegrass is one of those grasses that looks as good as it tastes. Livestock producers across the South heavily rely on annual ryegrass to feed cattle throughout the winter and early spring.

“Ryegrass pastures have been the backbone of the stocker cattle industry in the southern U.S. for many decades,” says Rocky Lemus, Mississippi State University extension forage specialist. “It is reliable and versatile; has a shiny, green appearance; and has tolerance to a wide range of soil types and conditions.”

Of its many desirable qualities, annual ryegrass is known for being a fast grower under ideal weather conditions. Lemus notes that its dense, but shallow, root system helps prevent erosion by enhancing water infiltration and improving soil tilth.

One of the annual ryegrass’ drawbacks is that performance declines un-der extended periods of high or low temperatures. Another disadvantage is that leaf rust can sometimes be an issue.

Several options

There are two main types of annual ryegrass to choose from: diploid and tetraploid.

“Diploid varieties tend to have narrow leaves, more tillers per plant, smaller seeds, and lower water content per cell, which could translate into higher dry matter yield per pound of feed and higher energy,” Lemus explains. “As a result, diploid varieties form a dense stand that is more competitive with weeds and can handle lower fertility and wetter conditions. Tillering also helps protect stands from animal trampling and weed competition. The stands tend to be more persistent and withstand heavy grazing densities,” he adds.

Tetraploid annual ryegrasses have wider leaves and larger seed size with higher water content. “These don’t tiller as much as the diploid varieties,” Lemus notes. “Due to the higher ratio of carbohydrates to fiber found in the tetraploid varieties, they could be more palatable to livestock and therefore improve intake and rumen function. However, keep in mind that tetraploids can have a higher water content, leading to lower intake compared to diploid varieties,” he cautions.

Lemus also explains that tetraploids could have a slower recovery than diploids, depending on environmental conditions and grazing management. Due to lower tiller density, tetraploids make a good choice for planting with clovers or other small grains because they are less competitive.

“Tetraploids could also make a good choice when interseeding summer perennial pastures like bahiagrass and bermudagrass,” Lemus says. “With less tiller density, they will let the warm-season grasses green up earlier in the spring compared to diploids.”

A third option to utilize annual ryegrass is to plant a blend of a tetraploid variety and a diploid variety. This option spreads risk across a wide range of weather and grazing strategies.

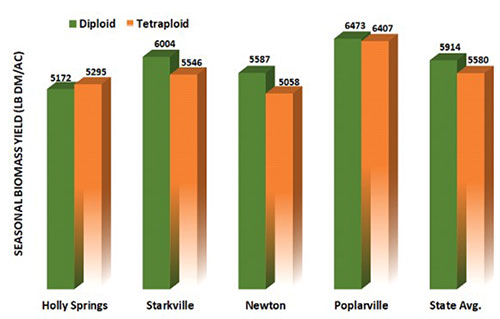

“Using a blend can provide the strong tiller growth and standability of the diploids combined with the leafiness and enhanced sugar content of the tetraploids,” Lemus explains. “Our data, collected over the last eight years, has shown very little yield advantage of tetraploids over diploids.”

Eight-year average yield comparison of diploid and tetraploid varieties

across four locations in Mississippi.

Lemus recommends to start inquiring about seed availability and seed cost now. The closer it gets to planting time, the lower the seed supply and the higher the cost of seed due to supply and demand. Tetraploid varieties tend to have a higher establishment cost compared to diploids because of the larger seed size and higher seeding rates.

How many acres?

Local weather conditions and type of livestock being grazed will determine how many acres to plant. Lemus notes that a well-established pasture of annual ryegrass can be stocked with 800 to 1,200 pounds of body weight per acre with proper moisture and proper fertilization.

These guidelines and stocking rates will vary depending on weather conditions, fertilization, and your grazing system. Lemus cautions that forage production will be limited by short, cold, or cloudy days.