Similar to that 30-year-old tattoo of an ex-girlfriend’s name that seemed like a good idea at the time, some things just hang around beyond their useful life.

The forage industry has several of these tattoos in the form of forage quality metrics that were thought useful in their day but have since been deemed inferior by new science and improved evaluation measures. The problem is that the old measures or calculations never seem to disappear.

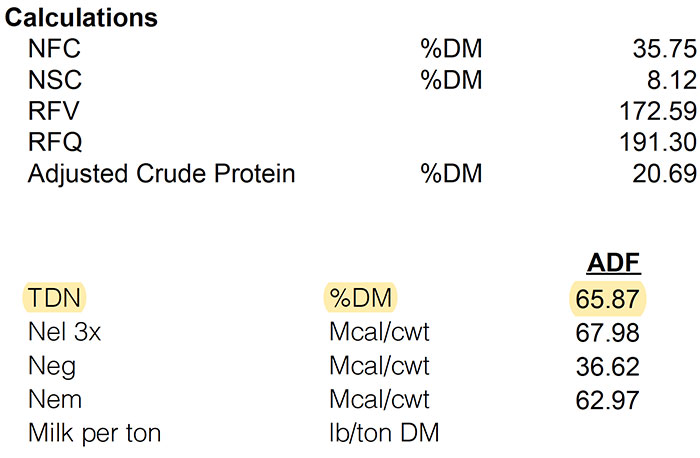

Exhibit A in the widely used but antiquated forage metric category is the use of acid detergent fiber (ADF) as the sole basis for calculating total digestible nutrients (TDN).

The alternative, and a much more accurate assessment of the livestock performance value of forage, is a summative TDN value, which is derived from adding together the digestibility of nonfiber carbohydrates (NFC), crude protein (CP), fat, and neutral detergent fiber (NDF).

Essentially, we have an old and new approach for calculating TDN that often offer different results. That’s a problem . . . a big problem in some cases. A similar comparison could be made between relative feed value (RFV) and relative forage quality (RFQ), with the latter being the summative approach that integrates forage digestibility.

Kudos to the American Forage and Grassland Council for assembling a panel of industry experts to discuss and seek solutions to this issue during the organization’s virtual annual conference. The panel included animal scientists, agronomists, and forage laboratory administrators.

Lisa Baxter, an extension forage specialist with the University of Georgia, began the discussion with an illustration of the problem. She referenced a bale of bermudagrass hay that was tested and found to be 49% TDN using the summative (preferred) equation. That same bale had a 63% TDN value when calculated solely from ADF. That’s a big difference.

“Both the NRC (National Research Council) dairy and beef nutrient requirement publications have gravitated toward the summative equation,” said Dave Combs, who recently retired from his position as a dairy scientist with the University of Wisconsin.

The NRC is widely accepted as the gold standard in terms of peer-reviewed nutrient recommendations and analysis for livestock feeding.

Combs noted that indexes are needed that will be valuable for all audiences, including dairy, beef, and commercial hay growers, and that TDN is one of those that works well for that purpose. However, an ADF-derived TDN falls short of predicting livestock performance in many situations compared to the summative approach.

“One of the initial problems was that some people used ADF to estimate digestibility, and it was never intended for that,” noted Dan Undersander, an emeritus extension forage specialist with the University of Wisconsin. “In fact, the research has shown that ADF is not a reliable estimate of digestibility. The value of the summative equation is that we’re looking at the digestibility of each of the major components of the forage. It’s not perfect, but at least we can use it across forage species and livestock classes,” he added.

Here’s the problem

A logical question to ask is “Why do labs still offer an ADF-derived TDN value if it’s simply not as accurate as the summative approach?”

“We are customer driven, so, for a lab, it’s not about being right or wrong,” said Ralph Ward, president of Cumberland Valley Analytical Services Inc. “We provide what the customer requests. That said, I feel the only real way to assign the most correct energy value is to use the summative approach.”

A significant number of farmers and industry professionals are still directly or indirectly requesting the ADF-derived TDN value. There are several reasons why this is occurring.

A lab report that is generated without forage digestibility measures (for example, NDF digestibility) will cost less, and this is what drives some customers’ requests.

“You’re being penny-wise but pound-foolish if you don’t request digestibility measures,” Undersander opined. “If farmers don’t use the equations that consider digestibility, they will never be able to see the advantage of improved forage genetics such as brown midrib hybrids, improved bermudagrass, or the reduced-lignin trait in alfalfa,” he added.

“Another problem lies in the fact that there are strong regional preferences for specific traditional indexes; for example, a lab cannot participate in the hay market in California without providing the California TDN, which is derived directly from ADF,” said Kyle Taysom, chief executive officer at Dairyland Labs, which has multiple locations throughout the U.S.

Something better?

Although TDN has long been used as a single forage quality index to assess livestock performance and the marketing value/grade for hay, perhaps there is a better approach.

“There is no one metric that is perfect, and we probably need to be looking at several,” said Dennis Hancock, director of the U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center in Madison, Wis. “The one I find most useful for single-term analysis is RFQ. It’s a robust, calculated equation that includes TDN, so having an accurate TDN estimate is still important.”

Taysom added, “In our labs, there is only one route to get RFQ. Although TDN is needed to calculate RFQ, it’s always done using the summative equation.”

Hancock, a former University of Georgia extension forage specialist, expanded, “RFQ is good for valuing forage, but if we are going to evaluate it for a fit within a ration or assessing market value, then we probably need four or five different values. For me, those metrics are RFQ, CP, TDN, NDF, NDF digestibility (NDFD), and some measure of physically effective fiber.”

Change is needed

If meaningful change and progress is going to take place, several actions need to occur. First, all forage producers and users must move into the 21st century and request only those lab analysis packages that include digestibility measures. This is the most accurate means of assessing forage quality. “The world is changing, and we aren’t doing much like we did 40 years ago except using some very old TDN equations,” Undersander said.

There needs to be a unified and meaningful effort in our extension and industry educational programs to explain why it so important to value forage based on digestibility measures. We need to get to the point where forage labs will no longer offer or report ADF-derived TDN and RFV because very few people are requesting or using them.

“We need universal nomenclature for identifying how values are calculated,” Taysom noted. “There is also a problem because labs use different ways to get a number for the same parameter.”

To address this issue, the panel agreed that a readily available reference library is needed to define exactly how various forage quality metrics should be calculated and reported.

Last, but certainly not least, the USDA Agriculture Marketing Service’s (AMS) hay grading system needs to be updated to reflect metrics that take forage digestibility into account. If the current hay market grades are allowed to stand, there will remain a demand for forage quality metrics that do not reflect digestibility.

“It’s not that labs don’t provide good information; it’s still critical to test forage and use a National Forage Testing Association lab,” noted Rocky Lemus, Mississippi State University extension forage specialist. “Our focus is to make it better than it already is.”

A collaborative effort, including multiple national forage organizations, will be needed for these changes to occur.

“We’ve been sweeping this issue under the rug for far too long,” Hancock concluded. “We can’t let perfect be the enemy of better.”