The positive benefits that legumes provide to pastures and animals are well known. Still, some graziers cite reasons for not maintaining a significant legume presence in their pastures. One of those reasons is the risk of animal bloat.

Bloat is the result of rumen gas production exceeding the animal’s ability to eliminate the gas. As the rumen swells with gas, it can eventually interfere with respiration. Depending on the diet, a large amount of foam or froth develops in the rumen and inhibits the release of gas, which causes the animal to bloat.

The bloat problem is compounded because more carbon dioxide is absorbed by the animal. Death from bloat generally is the result of suffocation.

“Bloat is often associated with discontinuous grazing, such as the removal of animals from legume pastures overnight,” notes Stephen Boyles, an extension beef specialist with The Ohio State University. “Pasture bloat may occur when grazing is interrupted by adverse weather, such as storms, or biting flies. Anything that alters normal grazing habits will increase the incidence of bloat,” he adds.

Legumes have highest risk

Alfalfa and many clovers are all highly digestible. The protein in these legumes is readily accessible to the rumen microbes. When these microbes digest the forage, they release gas. This gas mixes with liquids, which is how the froth and stable foam develops.

Environmental factors also contribute to bloat risk. This is why animals may be fine for weeks and then experience a high degree of bloat overnight while grazing the same or similar pastures.

Day temperatures around 70°F coupled with a cool overnight temperature will lead to a greater risk of bloating. High soil moisture, which results in high plant moisture, will also elevate the risk.

“Alfalfa can cause bloat in the spring, summer, and fall,” Boyles cautions. “Fall bloat conditions are caused by frequent heavy dew or fall frost. After a killing frost, alfalfa has a reputation of being bloat safe. However, if the plant stays green, the potential for bloat remains.”

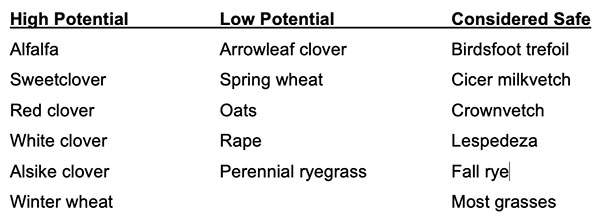

Boyles provides the following table that categorizes forage species as to their risk for causing bloat:

Two types

Bloat is often classified as being either pasture or feedlot bloat.

“It is more accurate to identify it as being either free-gas bloat or frothy bloat,” Boyles explains. “Frothy bloat normally occurs in cattle eating legumes or lush grasses. Free-gas bloat is less common in pastured cattle.”

The beef specialist provides the following recommendations for preventing bloat in pastured cattle:

1. Manage pasture for no more than 50% legumes. This has little value if selective grazing is possible.

2. Fill cattle on dry roughage or grass pasture before turning out on a legume pasture.

3. Do not initially turn cattle on pasture that is wet from dew or rain.

4. Once cattle are turned out on pasture, don’t remove them at the first signs of bloat. Watch them closely and remove only those whose condition continues to worsen, if it is a small percentage of the total number.

5. If greenchop is being fed, spread the intake over several feedings while the cattle are getting adapted.

6. Use livestock diet supplements that lower the risk of bloat. Anti-foaming chemicals like poloxalene can prevent pasture bloat for about 12 hours if consumed in adequate amounts. Begin feeding two to five days before turning onto pasture. Poloxalene can be fed as a topdressing, in a grain mix, in liquid supplements, or in molasses blocks. The blocks work best when scattered around the entire field at a density of about one block for every 10 head of cattle. They are are not as effective if placed only near the water supply. Because poloxalene is relatively expensive, some producers reduce the dosage or eliminate its use after several weeks. Feeding ionophores has also been shown to reduce bloat potential.