Hitting the desired harvest stage of maturity on any forage crop is difficult, but perhaps no class offers a greater challenge than small grains.

“Whatever stage you target, you’ll probably hit the next one,” said Mary Drewnoski, a beef specialist with the University of Nebraska. “Small grains work through their stages very quickly, and this may be the number one challenge of making cereal silages. One good rain event can delay you to the next stage,” she added while speaking at the Silage for Beef Conference.

Drewnoski and her research team have been doing extensive research to quantify the yield and forage quality tradeoffs for winter rye, triticale, and wheat.

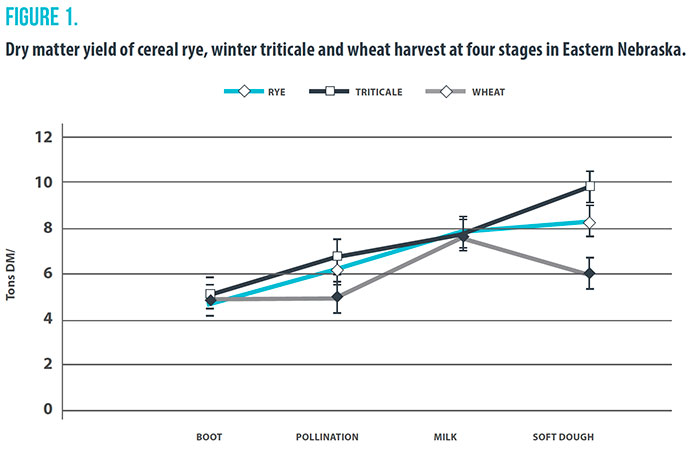

As expected, the dry matter yield of winter cereals increased linearly from the boot to milk stages. All three species yielded about 5 tons per acre at boot and about 8 tons of acre at milk. At soft dough, yield continued to rise for the rye and triticale but declined for the wheat because of leaf senescence.

“It was a little surprising to us that we didn’t see the rye and triticale separate themselves from a yield standpoint,” Drewnoski noted.

The energy content of the cereal forage was highest at the boot stage. All three cereals posted values between 55% and 60% total digestible nutrients (TDN). At the milk stage, TDN dropped to about 50% and then rose slightly as maturity advanced to soft dough because of additional starch content.

Crude protein (CP) declined from about 18% at boot stage to 11% or lower at soft dough. The small grains were fertilized with 40 pounds of nitrogen per acre.

“It should be noted that in warmer climates we typically don’t see this high level of protein,” Drewnoski said. “It’s also important to note that protein yield per acre was similar at all of the harvest growth stages. If you want to use these forages as a protein source, then harvesting early is the way to go; if you want yield, then harvest later,” she asserted.

Drewnoski noted that the small grains were harvested on the dates each species reached the target stage. She said they planted different varieties of rye and triticale in the two years of the study and found there was significant variability. “It looks like there is as much difference in maturity stage among varieties as there is among species,” the beef specialist said.

In summarizing her research, Drewnoski said that planting rye or triticale will generally result in the best nutrient yield per acre. She also noted that harvesting at pollination would boost yield over the boot stage without sacrificing much nutritive value. For maximizing TDN yield, harvesting at soft dough is a better option.

Aside from the harvest stage of maturity research that was done, Drewnoski pointed to survey results of 20 small grain silage growers in Nebraska. Samples of small grain silage were collected pre- and post-ensiling.

The take-home message from the survey results was that many producers were ensiling at moisture levels that were too wet — above 70%. This resulted in a significant loss in energy value during storage from clostridial fermentation. In one sample, the TDN value dropped by 17 TDN percentage units.

“It’s really important to harvest in that 65% to 70% moisture range,” Drewnoski concluded.