Cool-season annual grasses such as cereals and ryegrass are widely used at various times in the growing season, depending on location. In the South, they are often seeded in the fall for late-fall and/or early spring grazing. Many farmers also will make baleage out of these lush spring grasses as well.

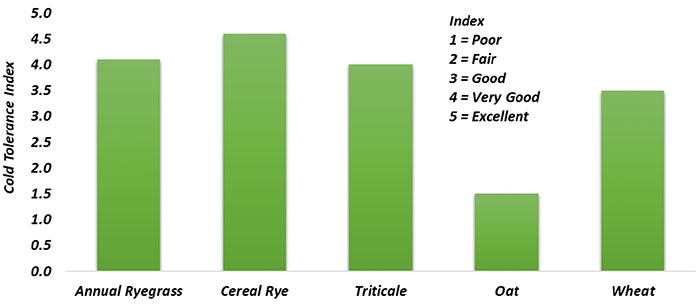

“Most cool-season annual grasses, except for oats, are well adapted to low temperatures but are still susceptible to winterkill,” says Rocky Lemus. The extension forage specialist from Mississippi State University notes that there are cold-tolerant variations between species (see graph) and between varieties within the same species.

Figure 1. Cold-tolerance index for cool-season grasses.

Winterkill is not just a weather-related phenomenon. Survival can also be dictated by abiotic factors and disease.

“Predicting winterkill is difficult because it can happen due to different factors such as low-temperatures, ice cover, desiccation, crown hydration, overgrazing and lack of canopy cover, inadequate soil fertility, stand age and health, or a combination of these,” Lemus notes. “The rapid decline in soil temperature below 20°F during freeze-thaw cycles favors low-temperature kill. In a cool-season annual forage system, most of the winterkill will be related to grazing management, heavy traffic areas, fertilization, low spots with poor drainage, shaded areas along fence lines, or having the canopy covered with ice for 10 days or longer.”

Plants need to acclimate

When the mercury dips in late December to late January, cool-season grasses undergo a dehydration process in response to gradually declining temperatures, shorter photoperiods, and cloudy days. This dehydration process raises the soluble content of the plant cells, including potassium and sugars. This allows the plant to acclimate to freezing temperatures.

“Low soil potassium, low pH, and overgrazing can delay the acclimation process and make forages more susceptible to the formation of ice crystals in leaves, shoots, and crown tissues,” Lemus explains. “Excess nitrogen fertilization can also promote cell expansion and growth, making the plant more susceptible to low temperatures and icy conditions.”

If plants become encased in ice, gas exchange between the leaves and atmosphere becomes compromised. This is sometimes referred to as anoxia. This situation limits the plant’s ability to get oxygen and toxic gases build within the plant. Lemus says the degree of damage may depend on the thickness of the ice, the duration of the ice on the surface, and the forage species.

Keep an adequate residual

“Desiccation and plant death can also occur when cool-season annual forages are exposed to a drying, cold wind for extended periods,” the forage specialist notes. “This condition is only observed when plants are overgrazed, and the exposed crown can lose tissue moisture where future new roots and shoots are produced.” Lemus recommends leaving a 6-inch residual stubble after grazing or waiting after establishment when plants are at least 8 to 10 inches tall before grazed.

“Crown hydration could be the most destructive type of cold-weather injury since this is the area where cool-season annual forages develop their root system and new shoots after grazing,” Lemus says. “This can often happen in late December to early February after periods of thawing and freezing.”

He explains that as temperatures start to warm and ice melts, forage plants begin to reacclimate and the crowns become hydrated. If a drastic freeze occurs during the thawing phase, then ice forms inside the crown and ruptures the cell membranes, causing loss of moisture and the formation of ice crystals between cells. This can be a common occurrence in lowland pastures or poorly drained soils where the soil remains frozen below the surface.

Lemus concludes by saying that it is difficult to prevent winterkill due to extreme weather; however, there are preventative measures that can lessen the impact. These include maintaining a good canopy cover, avoiding overgrazing, and maintaining good potassium levels to ensure winterhardiness.

Early planted, well-established forages that have undergone light or no grazing and are in the tillering phase will be less prone to winterkill and have the best chance of recovering from extreme winter weather. If stands are damaged, Lemus recommends limiting early spring grazing, leaving at least 3 to 4 inches of residual growth.