Alfalfa is often referred to as the “Queen of Forages” due to its value as a highly digestible, high-protein feed for dairy cows. It is one of the most environmentally friendly, sustainable crops on the landscape due to its ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen, enhancing the following crop in the rotation. However, this valuable trait wouldn’t be possible without rhizobia, which are special bacteria that live in soil or nodules formed on alfalfa roots.

Alfalfa forms root organs called nodules to house rhizobia, which transform inert nitrogen from the atmosphere into useable forms for the plant. This ability is key to the sustainability and yield of alfalfa, often used in farmers’ rotations to fortify the soil with nitrogen and improve soil health. Rhizobium inoculants are applied to alfalfa seeds to ensure they take advantage of this relationship. The best inoculants maximize the amount of nitrogen provided to their legume partner; this trait is called effectiveness. But rhizobia vary substantially in their ability to do this.

Different crop varieties respond differently to various strains of rhizobia. Therefore, as new varieties are developed, Barney Geddes, an assistant professor in the Department of Microbiological Sciences at North Dakota State University, thought it was important to identify a well-matched rhizobium partner that will maximize yield under nitrogen-replete conditions. Geddes was awarded a NAFA Alfalfa Checkoff grant for his project, “Identification of rhizobium inoculants tailored for performance with new alfalfa varieties and diverse soil types.”

“I have always been passionate about sustainable agriculture,” said Geddes. “Early in my career, I discovered the nitrogen-fixing symbiosis between legumes and rhizobia as the area I wanted to make an impact. While I studied symbiosis in the lab using alfalfa as a model for years, having grown up on an alfalfa farm I was keen to take on a project more directly tied to the field to help understand what is really going on with the symbiosis.”

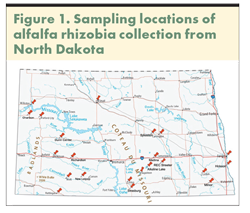

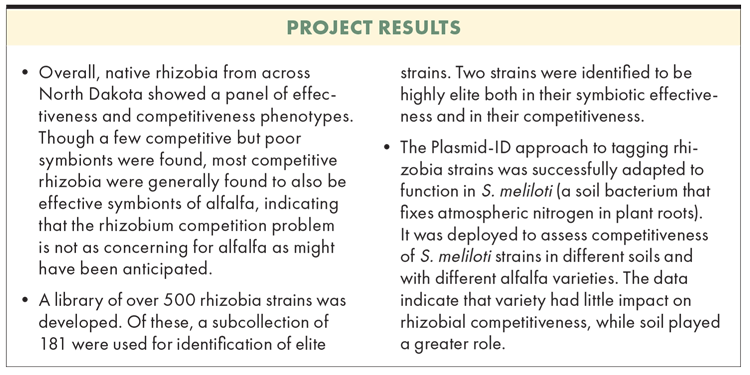

The overarching aim of the study was to understand the quality of rhizobia that are nodulating alfalfa in fields across North Dakota. “We think about quality in terms of two traits: effectiveness at providing nitrogen to the plant and competitiveness for occupying root nodules against other native rhizobia,” Geddes explained. “Competitiveness is important because there are many reports of native rhizobia being inferior to inoculant strains at providing nitrogen to the plant.

“What we found is the most competitive rhizobia from alfalfa fields across North Dakota are quite effective at nitrogen fixation. Farmers should feel comfortable utilizing the symbiosis for the nitrogen needs of alfalfa and avoid over-fertilization with nitrogen,” he added.

Geddes plans on continuing his research with interesting lines for follow-up study. “One area for further research is exploring the development of elite strains we developed as improved inoculants and finding the genetics in rhizobia that encode elite symbiosis traits,” Geddes said. “We are also very interested in thinking about the host genetics and if the plant can recruit more beneficial rhizobia in the soil over several years of cultivation with the right genes.”

A full copy of the final report can be found at https://alfalfa.org.

This article appeared in the January 2025 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 22-23.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.